Fixed Income Insights

Key Highlights:

- The US fiscal trajectory, marked by rising debt levels and structural deficits, is influencing global sentiment and prompting investors to reconsider the dominance of US Treasuries and the US dollar.

- Shifts in global capital allocation reflect the potential for gradual de-dollarisation, with implications for currency markets and portfolio diversification.

- Eurozone debt, driven by structural resilience, policy adjustments, and institutional backing, and emerging-market debt, supported by fiscal discipline and improving credit ratings, are gaining prominence as viable alternatives.

In a nutshell

Impact of US fiscal outlook on treasury market, dollar, and global sentiment

- The US federal debt is approaching levels last seen during World War II, driven primarily by structural fiscal challenges, including entitlement spending and rising net interest payments

- Efforts to address the deficit would likely require politically difficult reforms, making meaningful fiscal adjustments a challenging prospect

- At the same time, rising inflation volatility and higher interest rates are compounding the cost of US debt. This has contributed to an upward trend in the term premium on US Treasuries since 2020

- The fiscal outlook also has implications for the US dollar, which, while still dominant in global reserves, faces pressures from structural challenges like the twin deficits, alongside cyclical factors such as slower US economic growth and the broader narrative of de-dollarisation

- Foreign investors, particularly in Asia and Europe, continue to hold significant exposure to US assets. However, a potential shift in sentiment – whether due to fiscal concerns or global diversification efforts – could gradually lead to reallocations, potentially weighing on the dollar while supporting local currencies

What are the alternatives beyond US dollar denominated fixed income?

- As investors seek to diversify their fixed income portfolios beyond the US, Euro and Emerging Market debt are emerging as compelling alternatives, offering structural resilience and solid yields despite geopolitical and macroeconomic uncertainties

- Confidence in eurozone debt is growing, supported by structural resilience, policy adjustments, and institutional backing, even as geopolitical risks and market fragmentation persist

- Euro bond markets are further bolstered by increased foreign inflows, the eurozone’s transition to a net lender position globally, and stability provided by the EU’s institutional framework

- Emerging Markets also present attractive opportunities thanks to stronger fiscal discipline, stable public debt-to-GDP ratios compared to Developed Markets, favourable demographic trends, higher yields, and positive credit rating outlooks

Source: NATO, European Council, Centre for European Economic Reform, IMF, Bofa ICE indices, Moody’s rating, Macrobond, Bloomberg, HSBC Asset Management, May 2025.

The views expressed above were held at the time of preparation and are subject to change without notice. Any forecast, projection or target where provided is indicative only and not guaranteed in any way. HSBC Asset Management accepts no liability for any failure to meet such forecast, projection or target. This information shouldn’t be considered as a recommendation to invest in the particular countries and investments mentioned.

Impact of US fiscal outlook on treasury market, dollar, and global sentiment

The extension of the 2017 TCJA tax cuts plus some additional fiscal easing amid already poor deficit dynamics raises concern over US debt sustainability the US dollar's dominant role in global reserves and portfolios.

The secular trend of rising US debt, which is nearing World War II highs, is mainly driven by entitlement spending and net interest payments. The resulting wide fiscal deficit is an important driver of the current account imbalance, which has led to current trade tensions, especially with China.

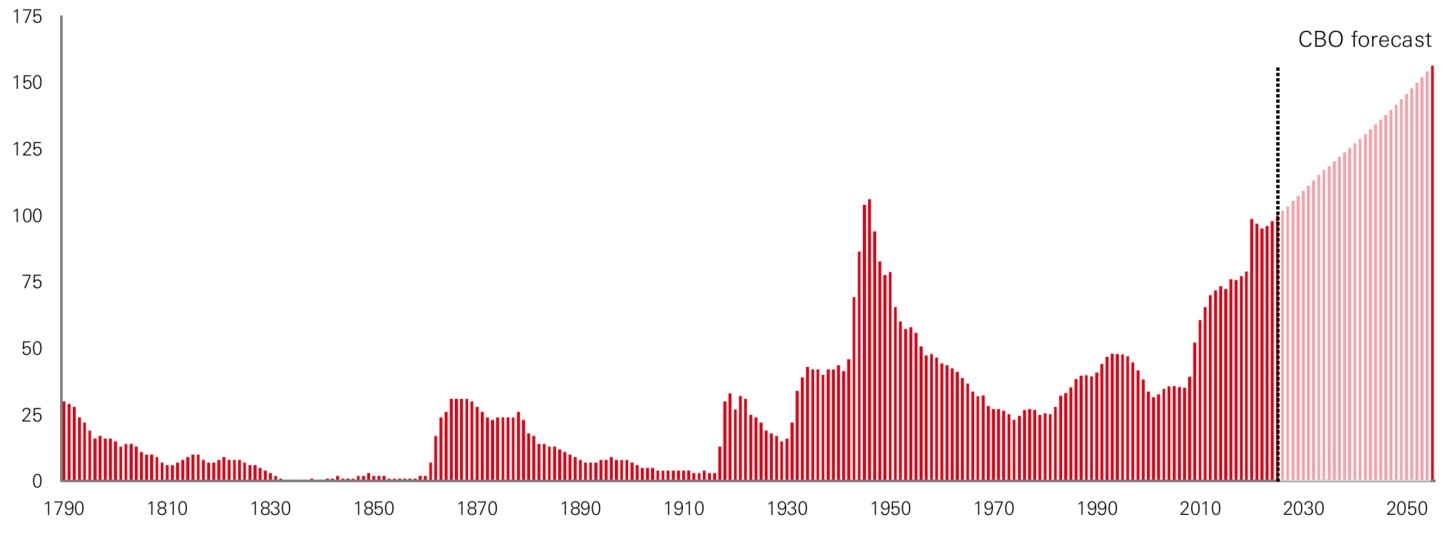

The recent fiscal history of the United States is marked by a secular increase in debt levels, approaching the peaks observed after World War II. This upward trend originated in the 1980s, with the late 1990s standing out as an exception due to robust productivity growth and targeted fiscal tightening measures. Since then, the trajectory of US debt has continued to rise, further intensified by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the Covid-19 pandemic. The underlying problems, however, are structural rather than cyclical or a function of economic shocks.

Figure 1: Federal debt held by the public (per cent of GDP)

Click the image to enlarge

Source: Macrobond, CBO, HSBC AM, June 2025

Source: HSBC Asset Management, June 2025. The views expressed above were held at the time of preparation and are subject to change without notice. Any forecast, projection or target where provided is indicative only and not guaranteed in any way. HSBC Asset Management accepts no liability for any failure to meet such forecast, projection or target.

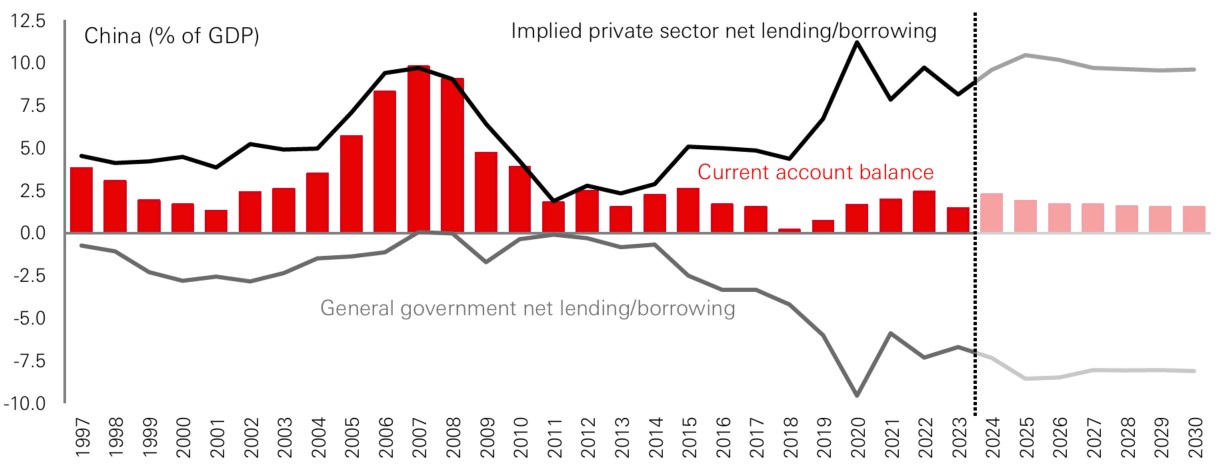

The US fiscal deficit is intricately linked to its current account deficit. A substantial government deficit, unless counterbalanced by a surplus in the private sector, inevitably leads to a current account deficit. External deficits have been a central theme of the President Trump administration’s trade policy, which has contended that unfair trade practices by other countries, notably China, have been solely responsible for US trade deficits. While China's current account surplus was extremely large in the early 2000s, recent years have seen a more balanced picture with China's government now incurring large deficits to counterbalance private sector savings. China has undoubtedly made significant efforts to stimulate private consumption, but this remains a key challenge for the economy, with the cultural preference for a high savings rate and the recent crisis in the real estate sector acting as obstacles to progress.

Figure 2: Government offsetting private sector retrenchment

Click the image to enlarge

Source: Macrobond, IMF, HSBC AM, June 2025

Domestic demand has also been generally tepid in Europe and the Trump Administration might somewhat legitimately argue that governments could do more to stimulate consumption so as to mitigate trade imbalances. Indeed, the recently-announced fiscal stimulus in Germany may be helpful in this regard. However, although non-US factors can help explain some of the US’s wide current account deficit, the fact that the US runs a government deficit of around 6% of GDP is a key reason why its external imbalances are so large and persistent.

The US federal deficit is driven by rising mandatory spending and net interest payments, alongside low tax rates. Demographic shifts, such as an increasing old-age dependency ratio, exacerbate fiscal challenges.

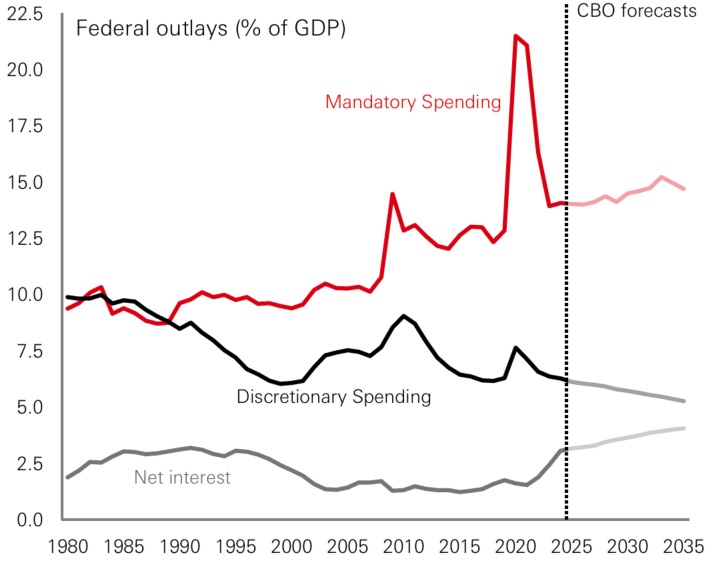

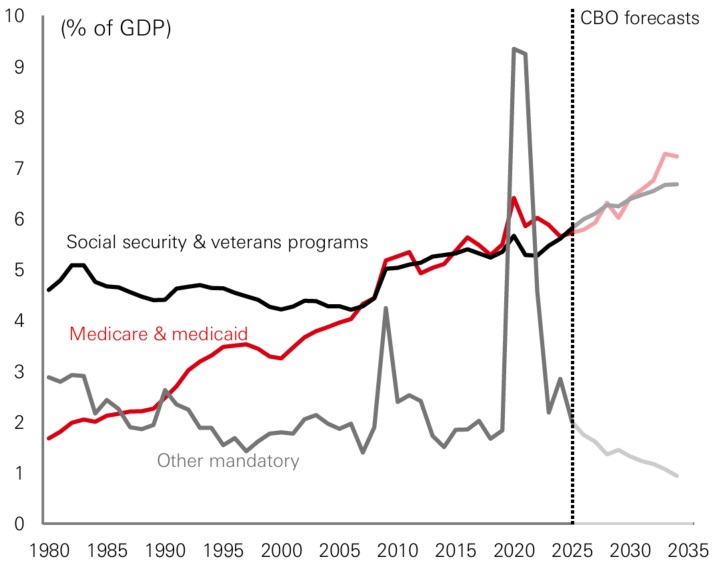

The widening US federal deficit has been driven primarily by rising spending in mandatory areas such as medicare and social security – so-called “entitlement spending”. Net interest payments have also increased due to rising debt levels and higher interest rates. Other discretionary areas of spending have actually declined as a share of GDP. Federal revenues have risen gradually as a share of GDP since 2010, but the US tax rate remains low compared to other developed nations. Ultimately, some combination of restraining entitlement spending or raising taxes is needed to correct the US’s deficit problem, but both are politically challenging.

Figure 3: No discretionary largesse

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 4: Entitlement spending doing the damage

Click the image to enlarge

Source: Macrobond, HSBC AM, June 2025.

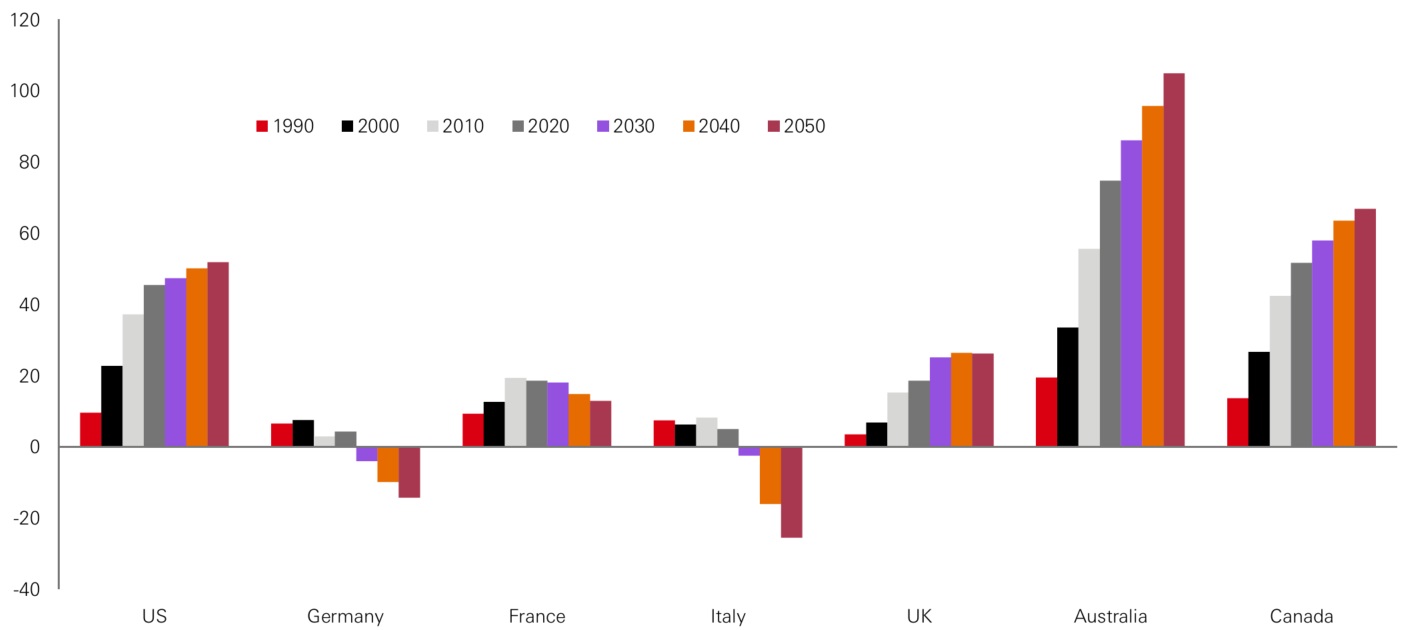

The US is not alone displaying poor fiscal dynamics – the UK, France and Italy also have high and rising debt levels. However, the US stands out because the deterioration in its public finances has occurred despite having more favourable demographics, highlighting the role of policy choices in the US. Moreover, the US’s demographic dividend is now coming to an end, adding to the pressure on the federal budget.

Figure 5: Change in population aged 15-64 from 1980 (per cent)

Click the image to enlarge

Source: United Nations, HSBC AM, June 2025

Addressing the deficit would require politically difficult reforms in entitlement programs, tax policy adjustments, and strategic debt management. There is little evidence that the current administration sees this as a policy priority.

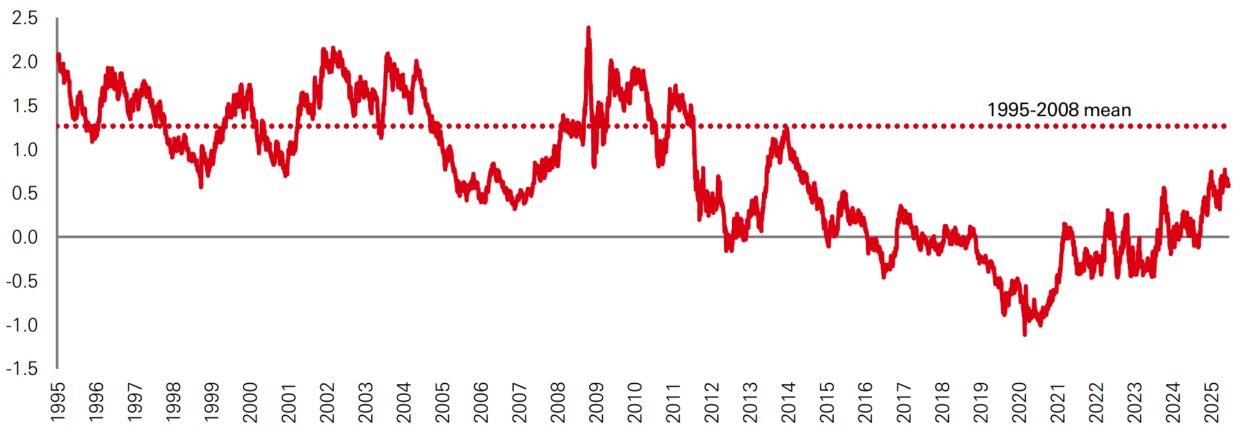

One of the key reasons why the fiscal trajectory has ended up on this path is that prior to the Covid pandemic, the US enjoyed very low short-term and long-term interest rates following the GFC, meaning that debt repayment costs were modest. Part of the explanation is that in the first two decades of the 21st century inflation was unusually low and stable compared to the 19th and 20th centuries. However, we now appear to be moving into a world where central bank inflation targets are more likely to be a floor than a ceiling for price increases and a greater proliferation of supply shock will generate more inflation volatility.

When combined with the deteriorating trend in public finances, investors are likely to require greater compensation for inflation and other risk involved in holding US public debt. Indeed, this already appears to be playing out with the term premium on US Treasuries having been on a rising trend since 2020. Nonetheless, the premium remains well below historical averages, suggesting further potential upside over the coming years.

Figure 6: Average of Kim-Wright and New York Fed 10y term premium estimate (pp)

Click the image to enlarge

Source: Macrobond, HSBC AM June 2025

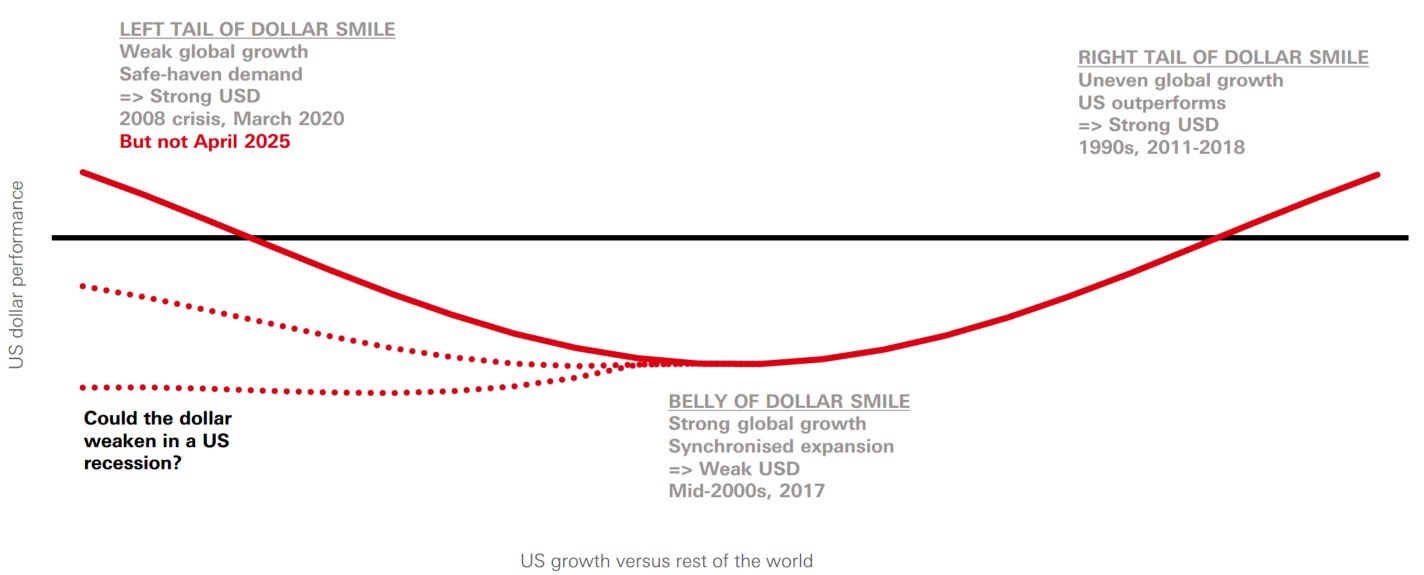

The US dollar's decline has been driven by the structural factors of high deficits and a growing narrative around de-dollarisation, alongside cyclical influences such as US growth slowdown and declining US exceptionalism. While the dollar remains dominant in the international financial system, its future will hinge on the evolution of these forces and their impact on debt sustainability and reserve diversification.

One of the primary structural challenges facing the dollar is the persistent twin fiscal and current account deficits. Despite this, the dollar has been strong in recent years, largely due to the perceived attractiveness of US assets and performance of markets, which has attracted substantial foreign capital inflows. Higher interest rates- particularly against the Euro and the Yen- have also been supportive.

The dollar's recent decline can be partly attributed to concerns about a US recession amid high policy uncertainty. Recent experience suggests that US policy uncertainty may weigh more on US growth rather than international growth. Meanwhile, international growth will likely get a boost by fiscal expansion in Europe and higher trend growth rates in Asia and emerging markets. This would likely encourage a diversification away from the US into other geographies. The dollar's behaviour in April 2025, when it moved contrary to rate differentials, highlights a potential shift in market dynamics. This divergence may partly reflect recently stated concerns about the credibility of US institutions and the independence of the Federal Reserve, consequently challenging the dollar's safe-haven status and its traditional role in global financial markets.

Figure 7: US dollar didn’t act as a safe haven during the equity sell-off

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, June 2025.

The "dollar smile" framework, which suggests that the dollar performs well during periods of US economic outperformance or global risk aversion, may become less reliable. There may be a spread of outcomes along the left tail of the smile – i.e. the safe-haven role of the dollar may not be guaranteed, and the greenback could decline during future risk-off episodes too.

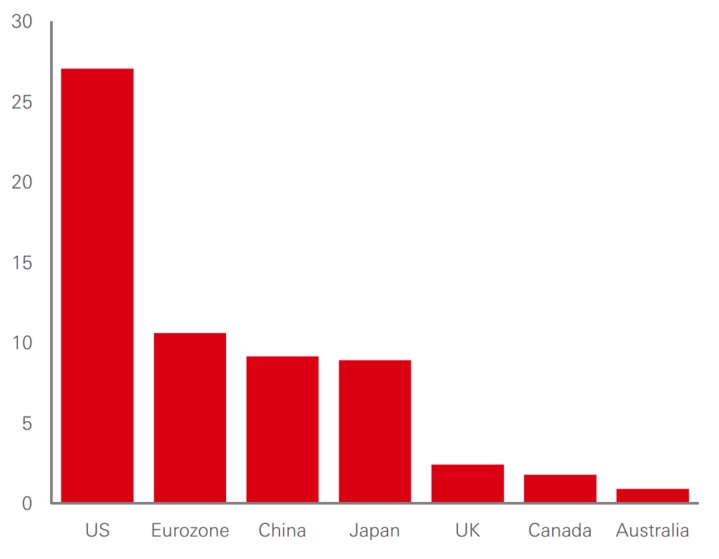

The dollar's share in global foreign exchange reserves has decreased from 65% in 2004 to 58% in 2024, reflecting a slow but steady diversification by reserve managers. While the euro and other currencies have not yet emerged as significant alternatives, the rise of gold as a reserve asset, particularly among emerging markets like Russia, China, and India, is a manifestation of the geopolitical and economic factors driving this shift. However, the absence of deep and liquid alternatives to US Treasuries remains a significant obstacle to rapid de-dollarisation, suggesting that the dollar will retain its dominant position in the near term.

Figure 8: Government bond market, USD trillion

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 9: Predicted change in net debt to GDP to 2030 (IMF Fiscal Monitor, per cent)

Click the image to enlarge

Source: IMF, HSBC AM, June 2025.

Asian and European investors maintain significant US asset holdings but shifts in sentiment could lead to reallocations, impacting the US dollar.

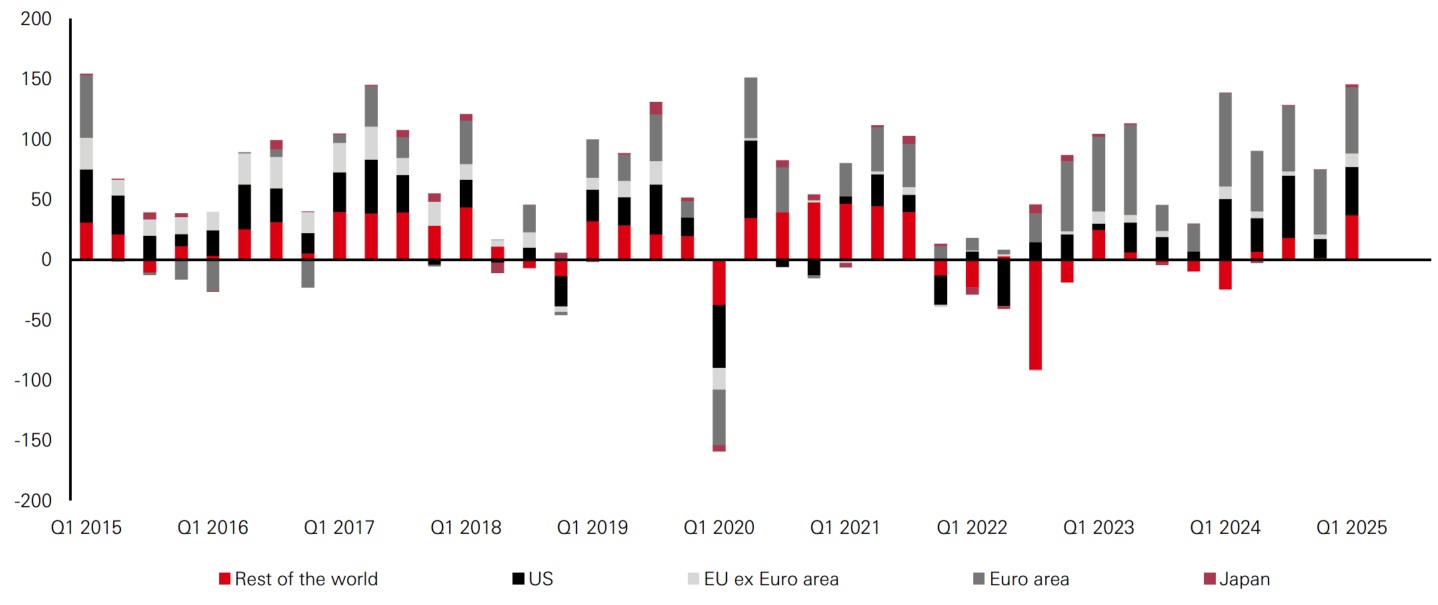

Foreign investors have significant exposure to US financial assets, exceeding $55 trillion by the end of 2024. Asian economies (excluding China) continue to invest heavily in US Treasuries, with regions like Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore increasing their holdings as of February 2025. Investments in US equities, particularly in the technology sector, have surged due to the AI and tech boom. This trend reflects the export-driven nature of Asian economies, which channel reserves into US assets, supporting the US dollar and asset prices. However, the concentration of global capital in the US implies that should sentiment toward US assets weaken, there is potential for a gradual reallocation into local assets. Such a move could weigh on the dollar and potentially support Asian currencies.

For instance, while China has maintained stable US Treasury holdings, its investment has not significantly increased since 2018, aligning with geopolitical tensions and tighter capital controls. At the same time, there’s a trend towards local currency bond issuance in Asia, driven by yield differentials rather than de-dollarisation. It is now more cost-effective for some Asian borrowers to raise capital in their own currencies than in dollar, as domestic interest rates have fallen and dollar interest rates have risen.

European investors reflect similar dynamics. Pension funds have increased their unhedged exposure to US equities, with assets close to USD 800bn by some estimates, and have benefited from the strong performance of the US dollar. However, just as in Asia, reliance on US assets poses risks if sentiment deteriorates, potentially leading to increased hedging or investment reallocation.

Any broad move away from US assets would likely be slow and gradual, primarily because there are currently no comparably large, deep, and liquid markets capable of absorbing this magnitude of capital. Thus, any de-dollarisation process will likely occur incrementally. Moreover, a sustained US dollar decline does not imply an end to its role as the world’s dominant reserve currency. There are multi-year episodes of secular dollar bear markets where the dollar retained its status as the pre-eminent global reserve currency (the 1970s, late 1980s and mid-2000s). Currency depreciation can reflect a revaluation of its strength due to macro, policy, and market dynamics. A falling dollar can thus coexist with ongoing reliance on it for trade settlement, reserves, and cross-border finance.

What are the alternatives beyond US dollar denominated fixed income?

Euro and Emerging Market debt offer diversification opportunities, supported by structural resilience and solid yields, despite geopolitical and macro uncertainties.

Foreign and domestic investment trends show renewed confidence in eurozone debt, driven by policy adjustments, structural resilience, and institutional support. These factors present compelling diversification opportunities and, although challenges such as geopolitical uncertainties and market fragmentation remain, the eurozone's evolving dynamics and institutional strengths enhance its appeal as an investment destination.

Since the euro's inception, its share of global foreign exchange reserves has fluctuated significantly. Initially rising from 18% to a peak of 28% in 2009, the euro's share fell sharply during the euro debt crisis, stabilising at around 19% since 2015. This decline highlights an important point: while global diversification away from the US dollar has occurred, the euro has not been a primary beneficiary.

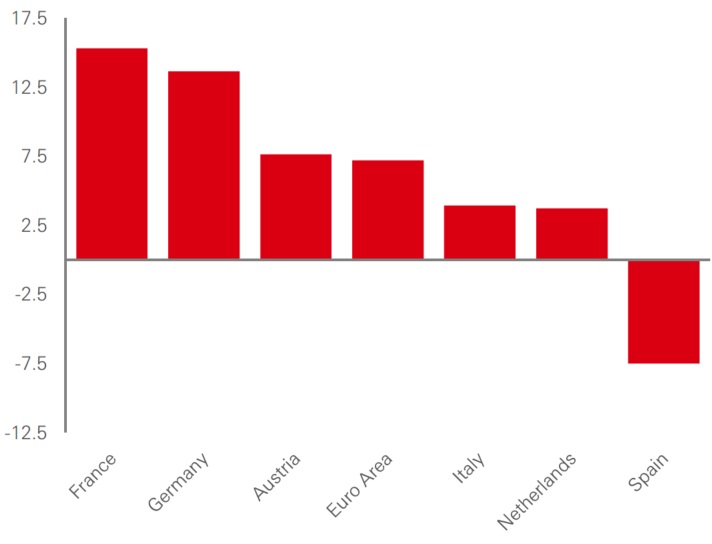

Foreign investment in eurozone sovereign debt has also seen notable shifts. Between 2010 and 2019, foreign investors held an average of 58% of eurozone government debt. However, this figure dropped to a low of 43% in 2022, before showing signs of recovery in 2023 and 2024. This rebound suggests a potential return of confidence in eurozone fixed-income markets, driven by factors such as policy rate adjustments and credit spread dynamics. Interestingly, foreign investors have historically shown a preference for euro-denominated debt securities over equities, particularly during periods of rising interest rates, such as in the late 2000s. However, the euro debt crisis and subsequent quantitative easing policies disrupted this trend, leading to reduced foreign participation until recent years.

Figure 1: Change in portfolio positioning (EUR bn) – Foreign holdings of EUR debt securities, equities and investment funds

Click the image to enlarge

Source: Bloomberg, HSBC AM, May 2025

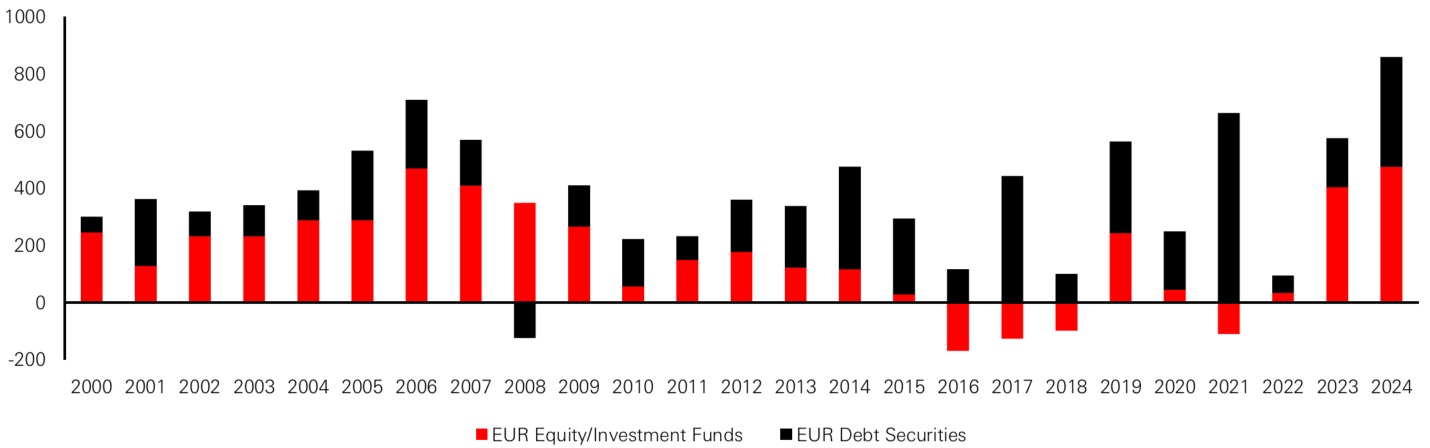

Domestic investors have historically reduced their exposure to euro-denominated debt securities, with their share falling from 68% in 2009 to 43% by the end of 2019. However, recent data indicates a renewed interest in euro debt securities among domestic funds, driven by the region's substantial pool of domestic savings. This shift highlights the growing attractiveness of euro-denominated assets for domestic investors, particularly in the context of declining policy rates and improving market conditions.

Figure 2: Debt securities held by eurozone investment funds – Flows by destination

Click the image to enlarge

Sources: Refinitiv, HSBC Fixed Income Research, HSBC AM, May 2025.

The strength of euro bond markets is underpinned by several structural and policy-related factors. For instance, Italy's sovereign debt market has demonstrated unexpected resilience despite political uncertainties and external shocks such as the energy crisis and the Ukraine war. Retail investors have played a crucial role, driven by specialised products offering inflation protection and loyalty bonuses. Additionally, foreign investment in Italian government bonds (BTPs) has surged, with inflows reaching €120 billion in 2024. This trend reflects a combination of rate differentials, political reforms, and structural factors unique to Italy, as well as other eurozone countries with accessible sovereign bond markets.

Another positive catalyst is the eurozone's transition to a net lender position globally since 2020, a significant shift from its previous status as a net debtor. This change, led by Germany, reduces the region's vulnerability to external financing shocks and sudden capital outflows. Positive net international investment positions are also viewed favourably by rating agencies, further bolstering the eurozone's attractiveness as an investment destination. However, the region's fragmented market structure and varying economic conditions across member states underscore the need for greater cohesion and institutional support. Meanwhile, policy attention is needed to address Europe’s lower potential growth rate against the US if it is not to continue to be an obstacle to investment.Nevertheless, The European Union's institutional framework provides a stable foundation for investors. The European Central Bank (ECB) has developed tools to manage market volatility, offering a greater degree of certainty. Additionally, EU funding programmes tied to pro-growth reforms, coordinated initiatives to address competitiveness gaps, and ongoing efforts toward a capital markets union contribute to the eurozone's appeal.

Emerging Market (EM) sovereign debt fundamentals have improved relative to those of Developed Markets (DM) as a result of fiscal discipline, de-dollarisation, favourable demographics, and narrowing inflation differentials, variously offering investors diversification and higher yields.

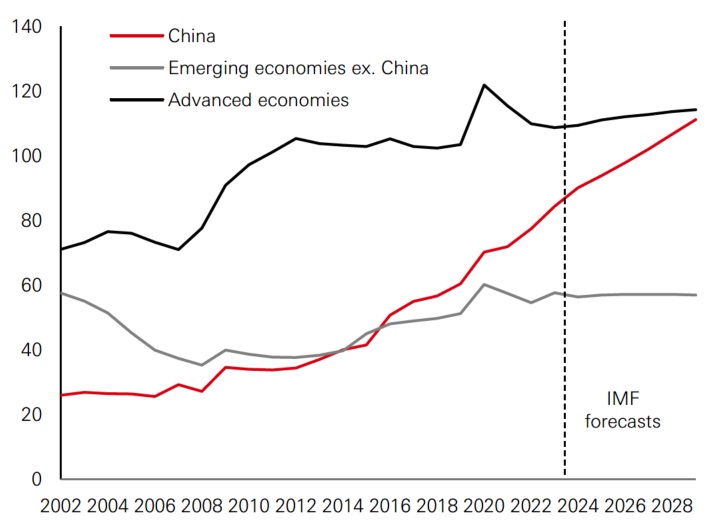

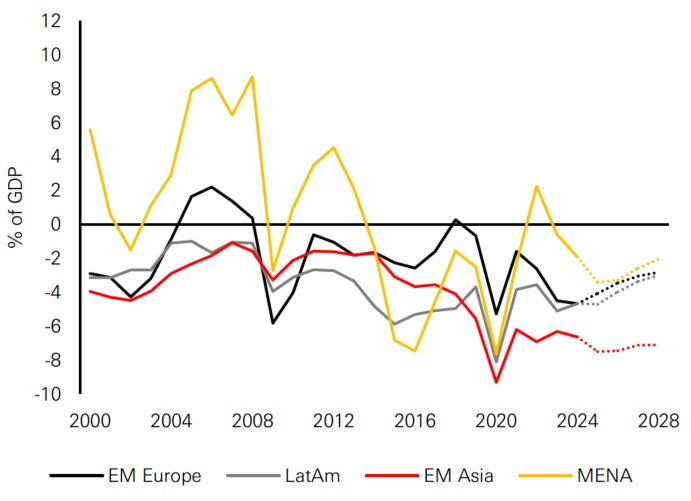

EM sovereign debt fundamentals have improved significantly relative to those of DMs over the past two decades. EM public debt-to-GDP ratios have remained broadly stable, while DM ratios have increased, significantly widening the gap. Excluding China, the difference in public debt-to-GDP ratios between EM and DM has grown from 14 to about 50 percentage points. As we might expect to see in such a diverse set of countries and regions, there has been considerable differentiation. While EM Asia, particularly China, has seen wider fiscal deficits, regions like Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and Emerging Europe have modest and improving budget balances. Several factors have contributed to the relative strength of EM public debt dynamics, including the de-dollarisation of a significant portion of EM debt reducing currency mismatch risks.Figure 3: General government gross debt (per cent of GDP)

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 4: Fiscal deficits to remain larger than pre-pandemic levels IMF government budget balance (per cent of GDP) projections

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, IMF, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, April 2025

In general, Emerging Markets have shown fiscal discipline in recent years and particularly post-pandemic, contributing to stable public debt. Lower primary deficits in EM countries are expected to persist, contrasting with Developed Markets, where interest liabilities have increased leading to higher debt burdens. Again, the picture is geographically nuanced, with EM regions such as Central America, the Caribbean, frontier economies, and hydrocarbon exporters demonstrating fiscal discipline, while deterioration is evident in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), China, Mexico, and Brazil.

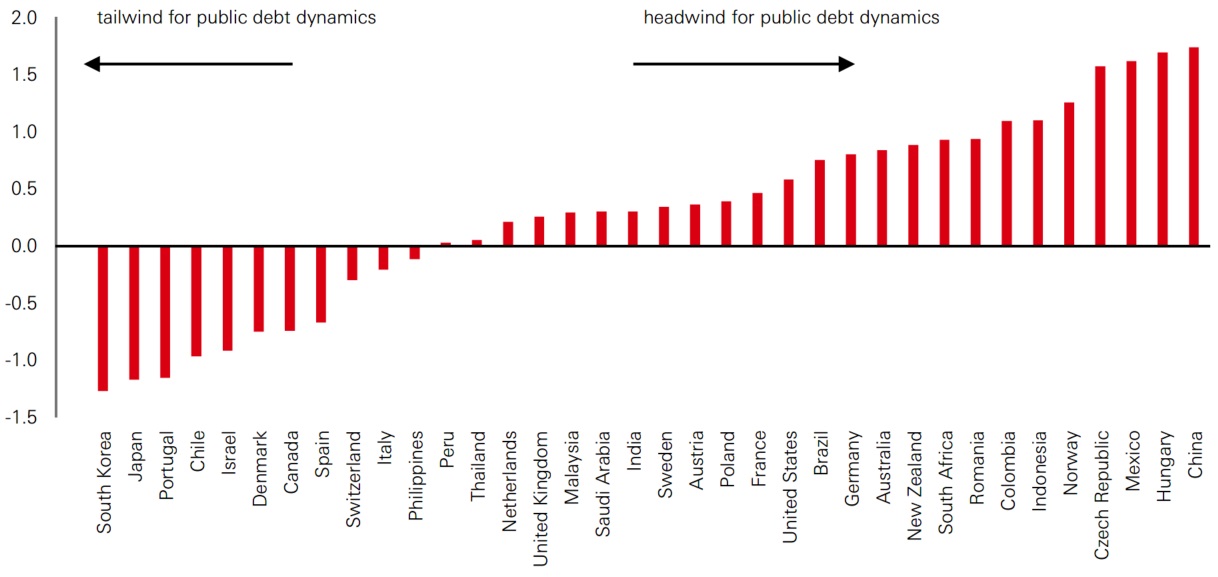

A useful measure of public debt sustainability is the relationship between the interest rate paid on debt (R) and nominal GDP growth (G). This metric determines whether a government can stabilize or reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio without running a fiscal surplus. A positive R-G score (where R exceeds G) creates a headwind for fiscal sustainability, while a negative R-G (where G exceeds R) provides a tailwind.

Figure 5: Change in R-G dynamics since the pandemic

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, IMF, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, May 2025

Since the pandemic, R-G balances have deteriorated globally, including in EM economies, due to rising interest rates and slowing nominal GDP growth. However, there are reasons for optimism regarding the R-G relationship in EM economies. Real rate differences between EM and DM economies remain wide, but inflation differentials have collapsed, providing scope for interest rates in EM countries to decline.

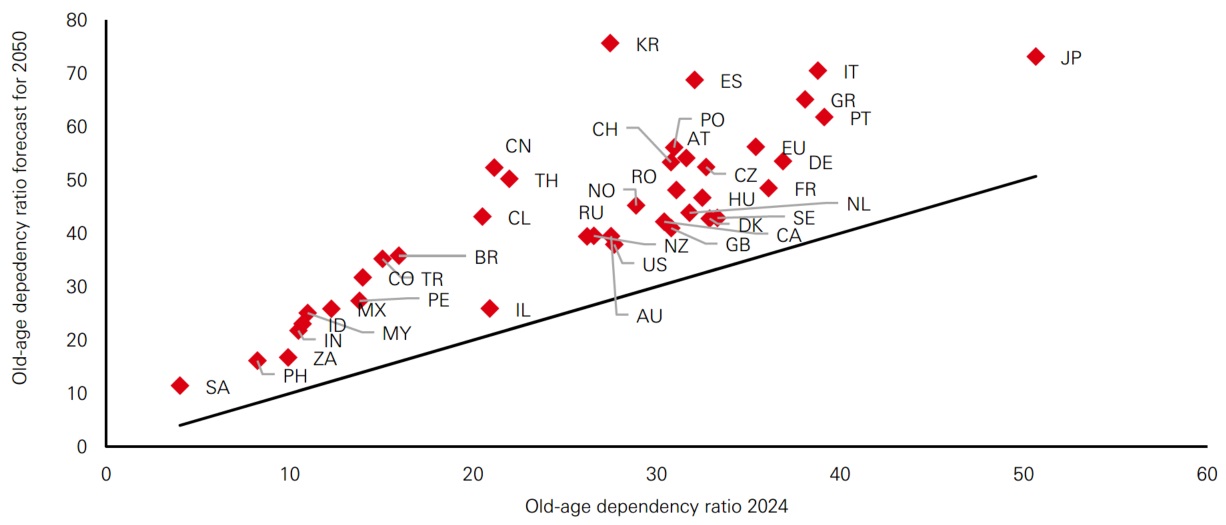

Demographic trends are another important factor influencing public debt in EM. EM economies generally have more favorable demographic profiles than DM, acting as a boost to economic growth and supporting debt sustainability over the long term. Countries like South Africa, many Southeast Asian nations, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia benefit from younger populations and growing consumer bases. However, not all EM regions enjoy these demographic advantages. Central and Eastern Europe face significant challenges, including aging populations and declining birth rates, which will weigh on growth potential and public debt.

Figure 6: Debt deficit and fiscal space

Click the image to enlarge

Source: Macrobond, IMF, HSBC AM, March 2025.

Historical data indicate a strong correlation between positive credit rating outlooks and subsequent upgrades. Currently, the balance of positive to negative outlooks in EM remains favorable, particularly within the BB cohort and frontier economies. Although central bank reserve managers have shown limited appetite for EM local currency assets as opposed to hard currency, the fundamental case for increasing allocations in the former is compelling. Rate differentials between EM and DM economies remain high while inflation differentials have collapsed in an environment where spreads across the USD bond complex are historically tight.

From a longer-term perspective, the relative improvement in EM public debt trends versus DM raises questions about the secular allocation of global capital. EM economies have demonstrated fiscal discipline in many regions, supported by IMF programs, debt restructurings, and favorable demographic trends. The size of the EM debt market, while smaller than the US Treasury market, still represents a significant opportunity. The total stock of EM hard currency public debt is approximately $1.8 trillion, compared to the $28 trillion US Treasury market.

Consequently, after a prolonged period of de-allocation from emerging market bonds, the technical positioning of investors is improving. From a starting position of low allocations, prudent debt management on the side of issuers can help maintain a relative scarcity of emerging bonds. Overall, we expect this trend to continue – and potentially accelerate – as ratings upgrades materialize – with over 20 EM countries on ratings watch positive, two-thirds of which will possibly receive upgrades in the near to medium term.

Source: HSBC Asset Management, July 2025. The views expressed above were held at the time of preparation and are subject to change without notice. Any forecast, projection or target where provided is indicative only and not guaranteed in any way. HSBC Asset Management accepts no liability for any failure to meet such forecast, projection or target. This information shouldn’t be considered as a recommendation to invest in the countries and investments mentioned. Diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against loss.