Multi-Asset Insights

In a nutshell

Global equities: Rethinking default settings

- The primary goal when using global indices is to reduce domestic market concentration risks. However, with the US comprising around two-thirds of major indices, they create a new concentration challenge

- To mitigate this concentration risk, one option is to implement selective tilts. Another is to adopt a blended approach that incorporates alternatives to traditional asset-weighted indices

- For example, combining market-cap weighting with fundamental, optimal, or risk-based methodologies can help reduce US and technology concentration

- Nonetheless, such approaches add complexity, pose implementation challenges, and require careful calibration

US Dollar’s dominance under scrutiny

- The US dollar remains the dominant global reserve currency but is facing increasing scrutiny due to US fiscal deficits, geopolitical tensions, and shifts in reserve compositions

- The dollar’s safe-haven status is also weakening, as evidenced by its diminished hedging power during recent market stress events

- Alternatives, such as gold and other currencies, are gaining traction, with central banks diversifying reserves to reduce reliance on the dollar

- As a result, investors must adapt their asset allocations to a more multipolar currency world and consider increasing allocations to gold, emerging markets, and non-dollar assets

Global equities: Rethinking default settings

Market-cap weighted benchmarks have resulted in nearly seven out of every ten dollars in a global equity portfolio being effectively tied to a single country: the US. This concentration is prompting asset allocators to rethink their approach to diversification.

US equities dominate the global equity landscape to a degree not seen in decades. With over 70 per cent of developed market equity benchmarks weighted towards the United States – double the share of the 1990s – multi-asset allocators face a profound dilemma. For some, it feels like riding a wave of US innovation and profitability. For others, it looks uncomfortably like a concentration risk waiting to unravel. The truth is, investors have been here before – when Japan dominated indices in the 1980s or when tech stocks ruled in the late 1990s. Each time, confidence in ‘this time is different’ was eventually tested.

In today's environment, exploring options beyond pure market-cap weighting isn’t about abandoning traditional benchmarks but rather about acknowledging their limitations. It means recognising that alternative approaches – such as GDP weighting, earnings weighting, equal risk contribution, or mean-variance optimisation – offer different perspectives for addressing concentration risks. The key question, however, is whether investors are comfortable with the current level of concentration or if it’s time to consider these alternatives.

Market-cap weighting as the default option

Market-cap indices, by construction, allocate the greatest weight to companies and countries with the highest market valuations. They emerged as a pragmatic solution in the mid-20th century when limited technology made calculating more complex metrics impractical. Over time, they became reinforced by the rise of passive investing, culminating in today’s dominance.

Their virtues remain clear: simplicity, transparency, and low cost. They allow investors to approximate market returns with minimal friction, explaining why they became the default benchmark for both institutions and retail investors. Yet the very qualities that made market-cap weighting so attractive are also the source of its weaknesses. By design, the vast majority of these benchmarks are concentration-agnostic. Investors end up allocating more capital to what is already expensive and highly concentrated, amplifying exposure to momentum-driven bubbles.

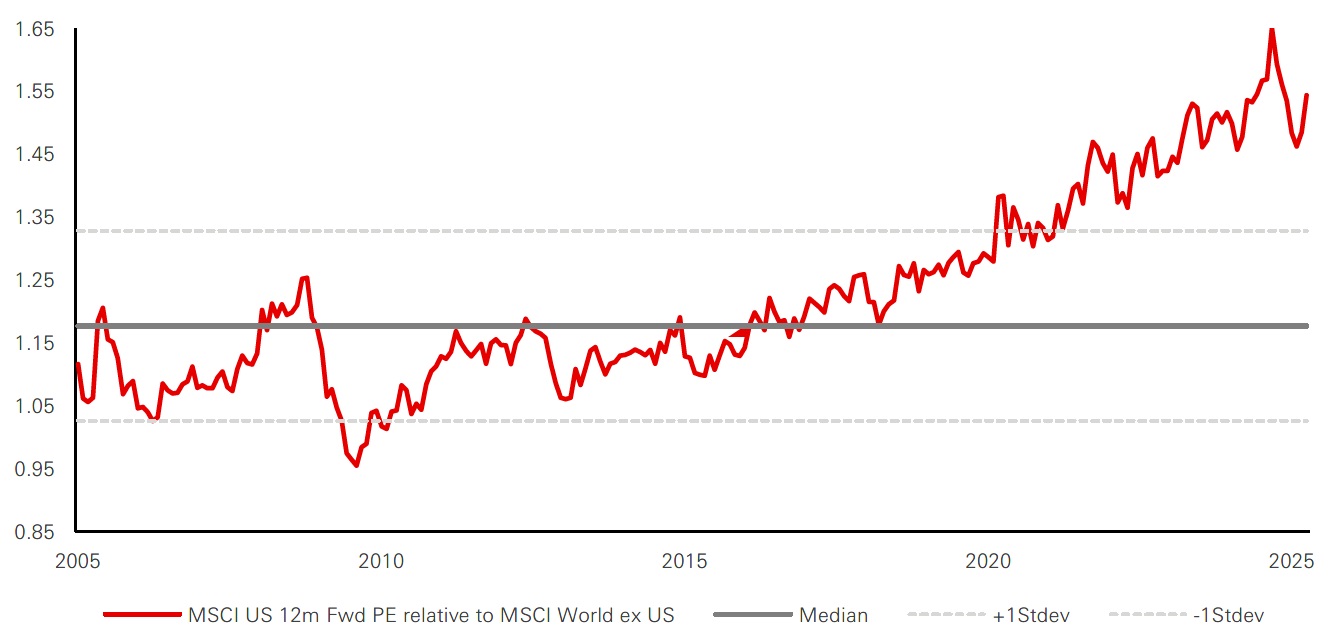

At present, this problem is most visible in US equities, where the rise of the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ mega-cap stocks has tilted global benchmarks towards an unprecedented concentration in a handful of companies. Trends in MSCI equity indices illustrate this growing concentration, and the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio highlights the valuation premium of US equities compared to other regions: US now trades at almost twice non-US CAPE valuation, further contributing to their elevated weighting.

US exceptionalism as a root cause

The dominance of the US within global indices is not merely a statistical anomaly; it is rooted in genuine economic and corporate outperformance. Earnings growth has been a defining force behind the US's increased prominence in global indices over the past few years. Driven by unique strengths in productivity, innovation, and corporate profitability, the US has consistently outperformed other markets. This growth has been supported by diverse factors, such as profit margins and asset turnover, showcasing the resilience and adaptability of its corporate sector. These attributes have firmly established earnings as a cornerstone of US exceptionalism.

Figure 1: 12M forward P/E of MSCI US relative to MSCI World ex US

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns.

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of August 2025.

This exceptionalism has been further reinforced by capital inflows, technological innovation, and structural advantages such as deep capital markets. As a result, the US justifies a premium – but the question is whether this premium has now become excessive. High valuations imply that forward returns may not match past performance. Extrapolating recent returns risks repeating historical episodes of disappointment, such as the reversal of Japan's market dominance in the 1980s or the subsequent downturn in emerging markets following their rapid rise in the mid-2000s.

Concentration matters beyond valuation

The concern isn’t just about whether US equities are expensive. It’s about what investors are actually exposed to when they solely follow market-cap benchmarks. The dangers of over-reliance on market-cap weighting go beyond valuation risk. Concentration distorts portfolios along multiple dimensions:

- Regional exposure: A heavy tilt toward the US leaves portfolios vulnerable to country-specific risks, including policy shifts, political instability, or a reversal in dollar strength

- Sector skew: Technology and financials dominate market-cap benchmarks, creating additional cyclical vulnerabilities

- Style bias: By construction, market-cap weighting favours growth and momentum at the expense of value

- Currency exposure: A 65–70 per cent allocation to US equities implies a significant overweight to the US dollar, amplifying FX risk for global investors

Taken together, these ‘hidden’ exposures challenge the principle of diversification, which remains the cornerstone of multi-asset investing. For allocators, it is becoming increasingly important to explore potential alternatives to reduce reliance on pure market-cap indices.

Exploring alternatives to market-cap weighting

There are a range of alternatives to market-cap weighting, each with distinct strengths and trade¬offs depending upon the approach it follows.

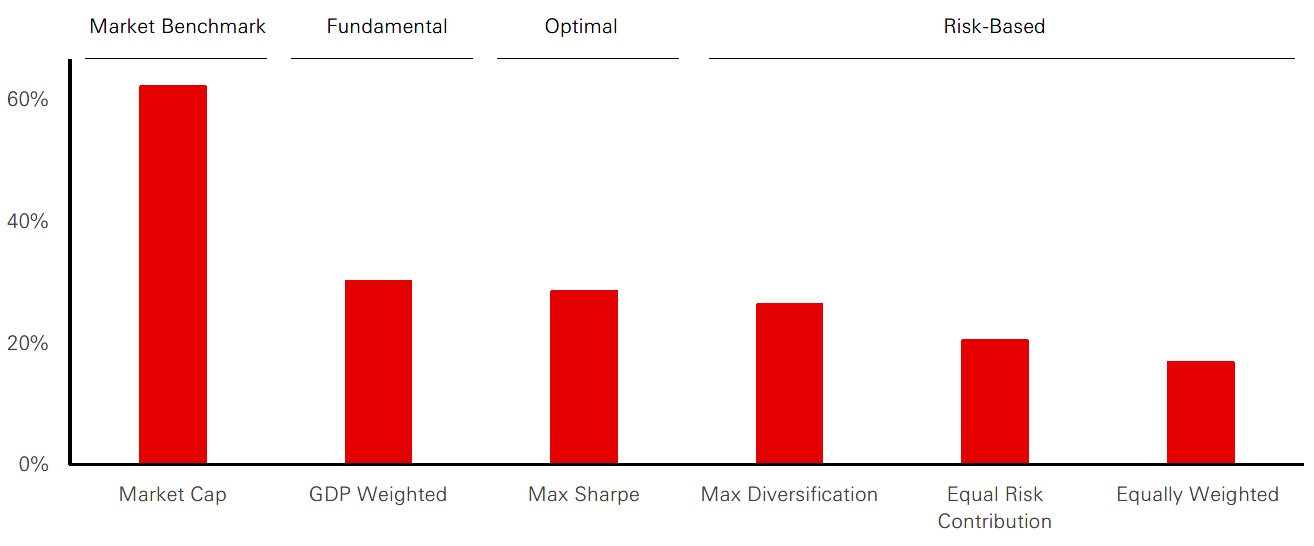

Fundamental weighting indices do not rely on valuations. Instead, they aim to reflect economic representation, as opposed to being driven by market-related data. Among this category of indices, GDP-weighted indices allocate equity weights based on a country’s share of global GDP. By design, this approach grounds portfolio exposure in the real economy rather than in market valuations. Under such a framework, the weight of the US drops from roughly 62 per cent to about 30 per cent, bringing emerging markets – particularly China – into greater prominence.

While sensible in theory, GDP weighting faces challenges such as data revisions, higher turnover, and historically weaker performance compared to market-cap indices. Similarly, earnings-weighted indices assign greater weight to companies that generate higher profits. This approach is intuitively appealing because it ties capital allocation directly to fundamental corporate performance. However, profits are cyclical and volatile, which means earnings-weighted indices can fluctuate sharply in response to economic cycles, reducing their overall stability.

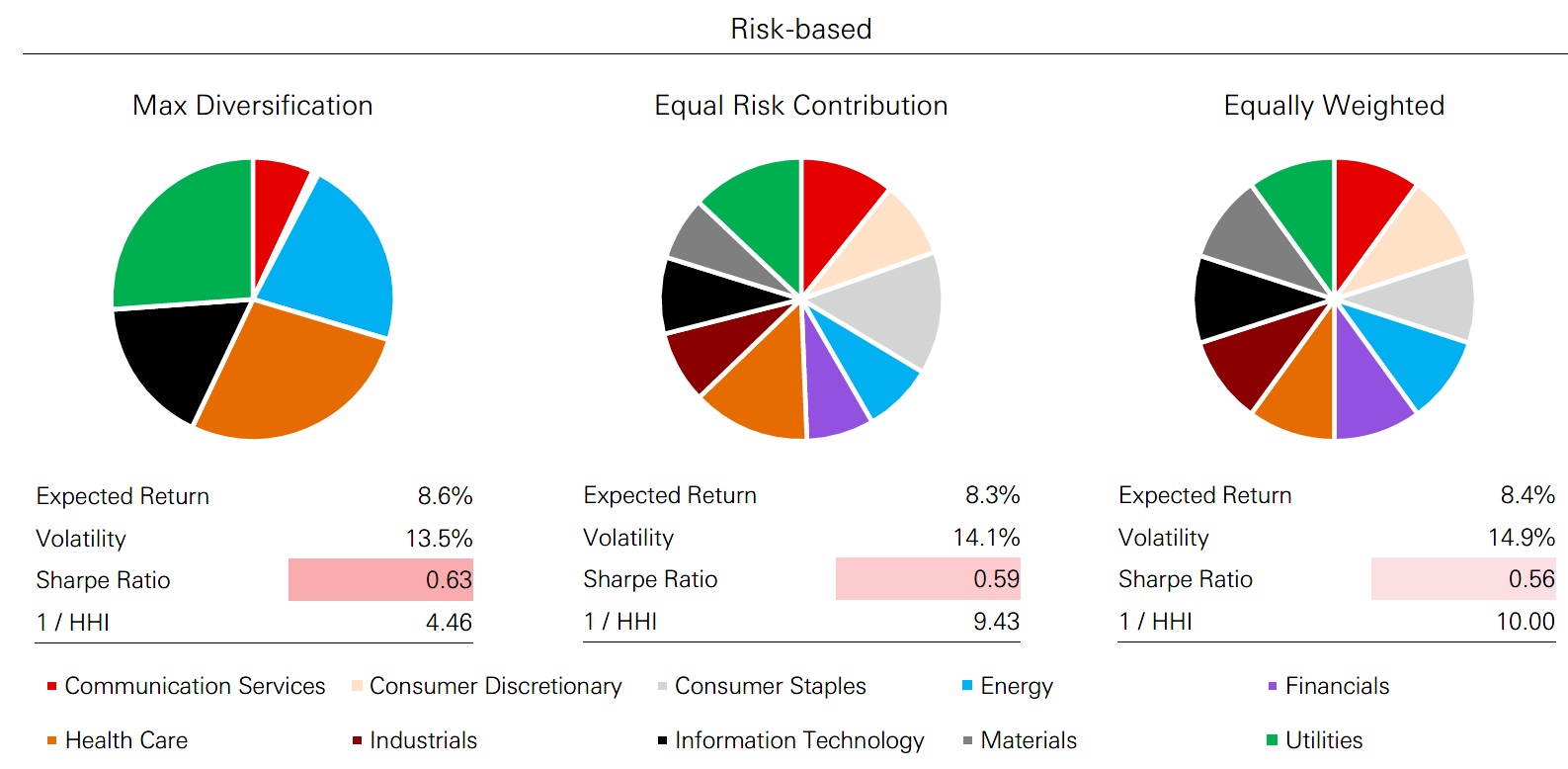

Another approach involves risk-based methods, such as equal risk contribution (ERC) and maximum diversification, which aim to distribute risk more evenly across holdings. ERC portfolios allocate risk proportionally, while maximum diversification gives more weight to assets that diversify the portfolio the most. These strategies tend to provide better diversification and often outperform market-cap indices on a risk-adjusted basis. However, they are associated with higher turnover and potential unintended biases.

Finally, mean-variance optimisation techniques seek to maximise risk-adjusted returns based on capital market assumptions. In practice, these portfolios often exhibit significant tilts towards specific markets or sectors, driven by historical correlations. For instance, in one exercise, the Max Sharpe portfolio allocated a disproportionately large share to Japan due to its favourable return expectations and low correlations. While theoretically "optimal," such solutions can be unstable, highly sensitive to input assumptions, and prone to corner outcomes.

Each of these approaches changes the shape of the portfolio. When applied to regional allocations, all alternatives reduce the US weight substantially, typically to between 15 per cent and 30 per cent. This not only diversifies geographic risk but also increases exposure to emerging markets and Europe. Interestingly, despite different methodologies, the consistency across alternatives is striking – suggesting that market-cap indices may currently allocate disproportionately to the US.

Figure 2: US weighting by approach

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM. Data as of September 2025.

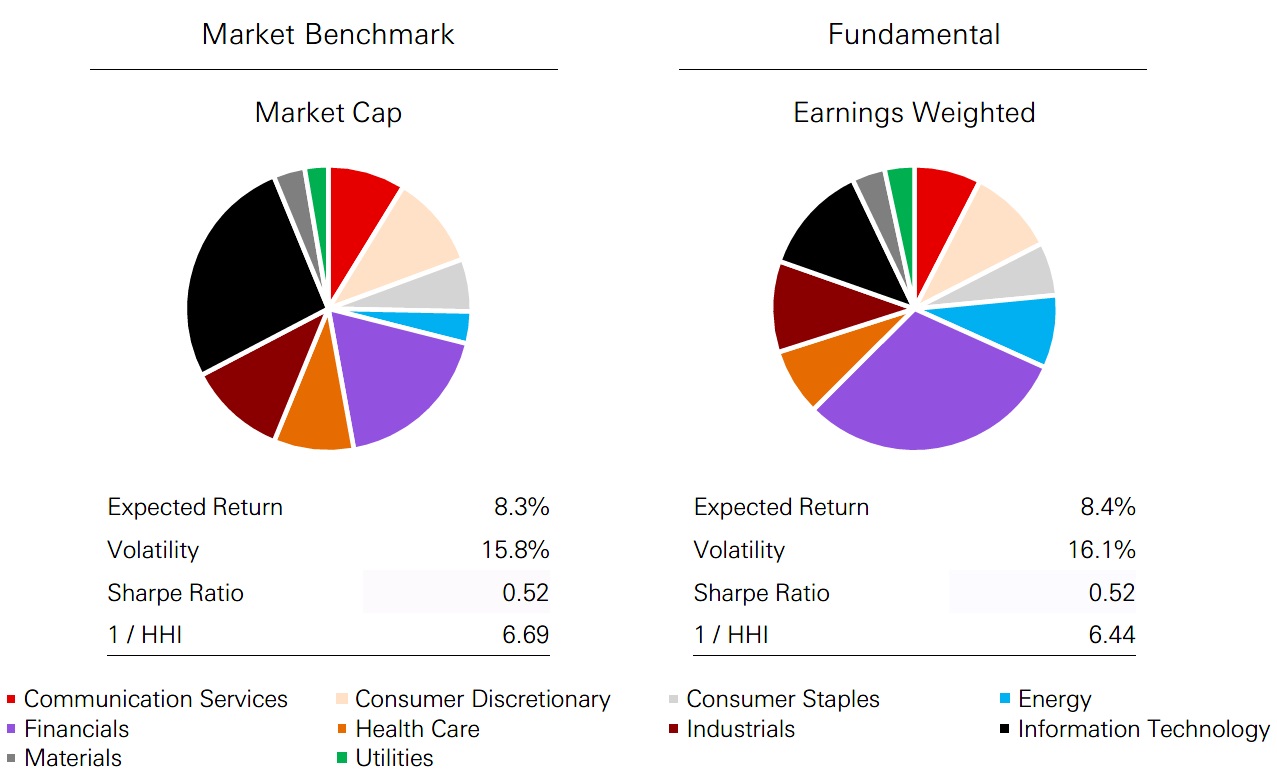

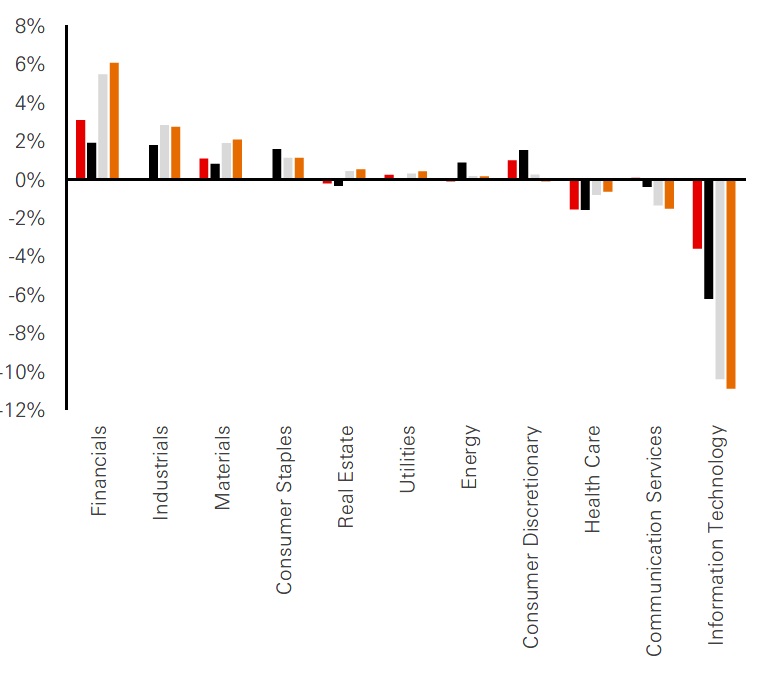

At the sector level, alternatives reconfigure exposure in important ways. Earnings-weighted indices, for instance, shift allocation towards financials, reflecting the sector’s outsized profit generation. Risk-based approaches, meanwhile, spread risk more evenly across sectors, reducing dependence on technology and creating a more balanced portfolio profile. While none of these approaches are perfect – they come with turnover, cyclicality, or quirks of their own – they highlight how concentration in market-cap indices is not just regional but also sectoral.

Figure 3a: Sector allocations by approach

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 3b: Sector allocations by approach

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM. Data as of September 2025.

Testing the implications of shifting to alternatives

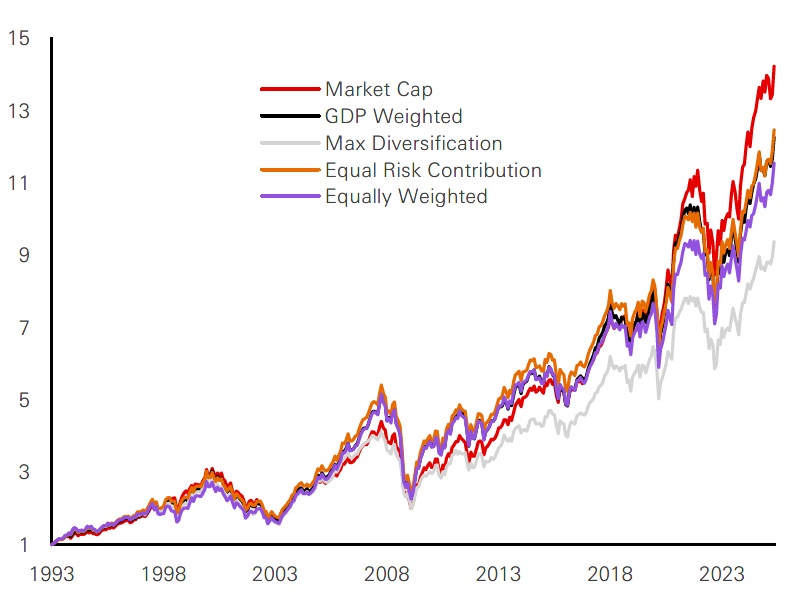

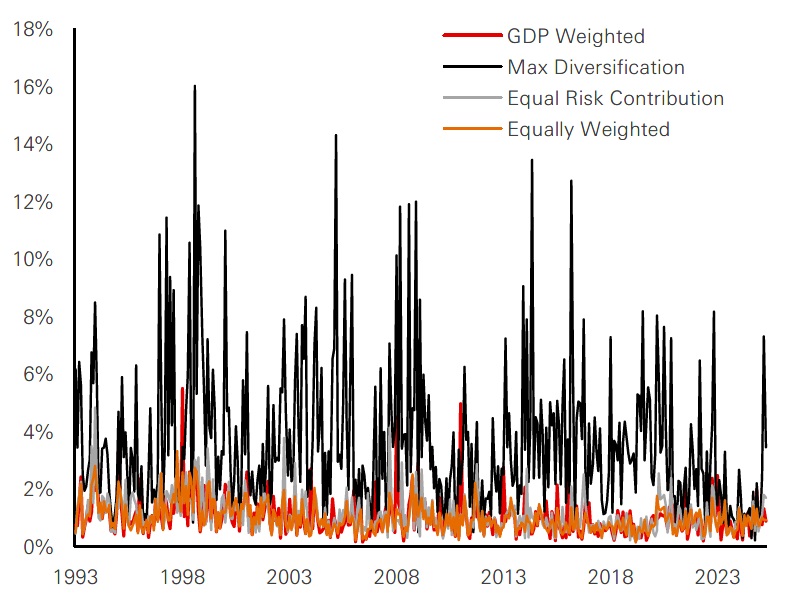

A 30-year backtest shows that market-cap weighting has indeed outperformed most alternatives— but crucially, this outperformance has been concentrated in recent years, driven by US mega-cap technology stocks. Historically, alternative weighting schemes such as ERC and equal weighting have delivered more consistent diversification and smoother drawdown profiles. Max diversification, while unstable, demonstrated resilience in certain downturns, though at the cost of high turnover.

Figure 4: Historical performance of regional portfolios (USD)

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 5: Turnover for regional portfolios

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns.

Source: HSBC AM. Data as of September 2025.

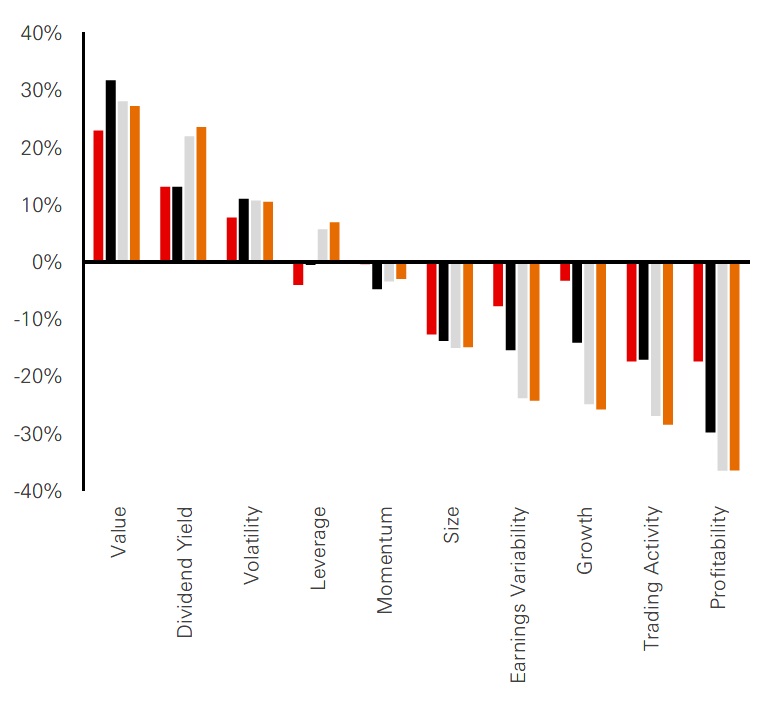

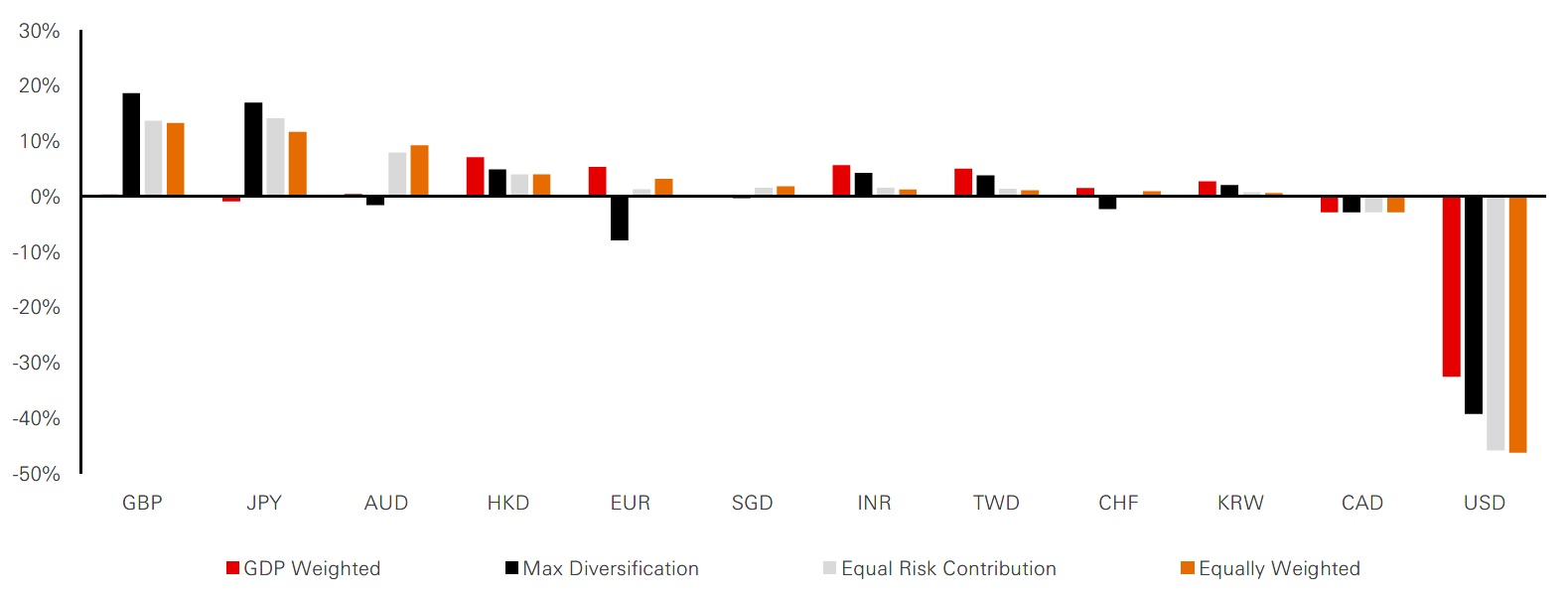

The key takeaway is that market-cap indices’ recent dominance may be more of a cyclical phenomenon than a structural inevitability. Moreover, shifting away from market-cap weighting is not a neutral choice. Alternatives carry implicit tilts such as:

- Sector tilt where financials were overweighted, and technology underweighted

- Style tilt where the approach went long value, and short growth and momentum

- Currency tilt which reduced exposure to the US dollar

These tilts are not necessarily disadvantages but must be recognised and managed. For instance, reducing dollar exposure may appeal to investors concerned about the sustainability of US fiscal policy, while a tilt towards value could provide diversification against growth-driven drawdowns.

Figure 6: Sector active exposures

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 7: Factor active exposures

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 8: Currency active exposures

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns.

Source: HSBC AM. Data as of September 2025.

An evolution more than a revolution

The global equity market has reached an inflection point. While market-cap indices remain indispensable, they now carry risks that are becoming harder to ignore, such as excessive US concentration, sectoral imbalances, and heightened valuation sensitivity. Alternatives like GDP weighting, earnings weighting, risk-based allocation, optimisation techniques, and hedging strategies each offer potential ways to address these challenges, though none are without trade-offs.

For investors, one possible approach could be to blend alternatives with market-cap indices rather than replacing them entirely. For instance, combining market-cap weighting with methods such as ERC or maximum diversification in varying proportions might help to gradually reduce US and technology concentration. However, such blended strategies are not a one-size-fits-all solution. They introduce complexity, require careful calibration, and may not deliver the same simplicity or scalability as pure market-cap indices. The benefits of reduced dollar exposure and sector concentration need to be weighed against potential implementation hurdles and the risk of departing too far from benchmarks.

The key takeaway is not necessarily to discard market-cap indices but to consider supplementing them thoughtfully – while being mindful of the additional complexity and potential unintended consequences of alternative approaches.

For multi-asset investors, the primary objective of using global indices in their allocation is to diversify their investments. Diversification helps mitigate the risks associated with concentrating investments in domestic markets and creates more robust portfolios.

However, with the US now accounting for over two-thirds of the most widely used indices, relying on global indices simply replaces one concentration issue with another. Asset allocators cannot afford to overlook this risk. To achieve greater diversification, they need to explore alternative strategies. One option is to implement selective tilts. Another is to adopt a blended approach that incorporates alternatives to traditional asset-weighted indices.

US Dollar’s dominance under scrutiny

As the US dollar faces structural headwinds, such as fiscal imbalances and geopolitical tensions, investors must prepare for a world where it may continue to hold a strong position, but its dominance is no longer unshakable.

For more than seven decades, the US dollar has reigned supreme as the world’s reserve currency. It anchors global trade, underpins financial markets, and provides the United States with unparalleled borrowing advantages. Yet, with political pressures on the Federal Reserve, widening fiscal deficits, and shifts in global reserve composition, questions are emerging about whether the dollar’s dominance is beginning to erode. While the dollar remains indispensable, cracks in its supremacy are more visible than ever. In fact, the rising interest in alternatives like gold, which once backed dollar, suggest that the greenback is entering a more complicated phase.

The US dollar’s dominance began in 1944, when 44 Allied nations agreed at Bretton Woods to peg their currencies to the dollar, itself backed by gold at USD 35 an ounce. The United States was uniquely positioned for this role, holding two-thirds of the world’s gold reserves and commanding the strongest postwar economy. Even after President Nixon severed the dollar’s link to gold in 1971, the greenback’s primacy endured. The US-Saudi oil deal of the early 1970s cemented demand for dollars by ensuring oil was traded exclusively in USD, creating the ‘petrodollar’ system.

Figure 1: US gold reserves (in per cent of total gold reserves)

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg, IMF. Data as of September 2025.

Beyond these foundations, the US offered deep capital markets, political stability, and legal protections unmatched by other nations. These factors, often referred to as the ‘exorbitant privilege’ of the dollar, made it the unrivalled reserve currency and allowed the US to borrow cheaply while others bore the burden of accumulating dollar reserves.

Characteristics of a global reserve currency

In order to serve as a global reserve currency, a currency must meet several criteria. It must be:

- backed by a large, stable economy;

- supported by deep, liquid capital markets;

- fully convertible;

- anchored by strong institutions and an independent central bank; and

- widely used in trade and finance

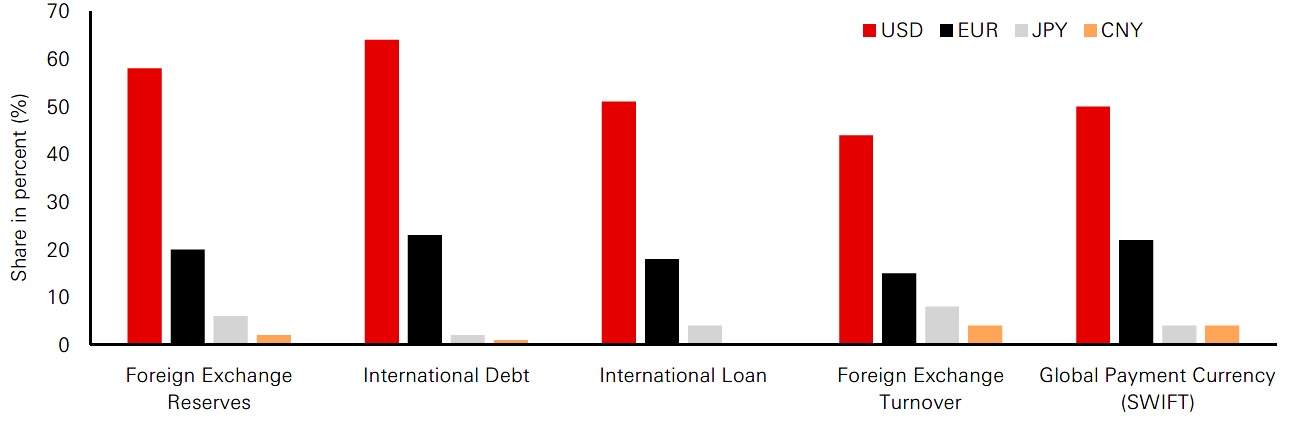

The dollar remains the only currency that continues to meet all the conditions of a reserve currency better than any rival. In comparison, the euro suffers from fragmented fiscal governance. The yuan is constrained by capital controls. Smaller currencies such as the yen or Swiss franc lack scale. While alternatives like cryptocurrencies and gold are growing, they remain far from matching the dollar’s breadth of use. Furthermore, network effects come at play as the more the dollar is used, the harder it becomes to dislodge.

Figure 2: Use cases of different currencies

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg, US Treasury, US Fed, ECB, IMF COFER, SWIFT, BIS, Atlantic Council, September 2025.

De-dollarisation and signs of strain

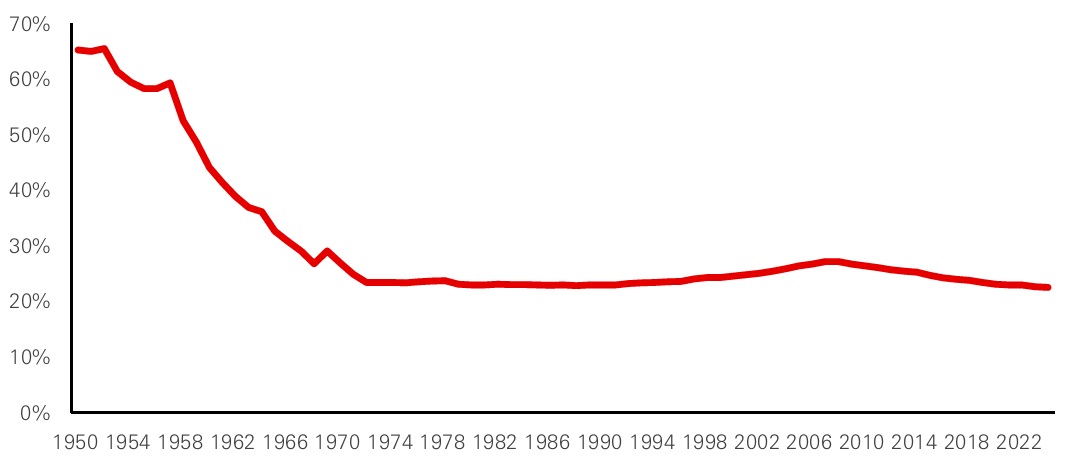

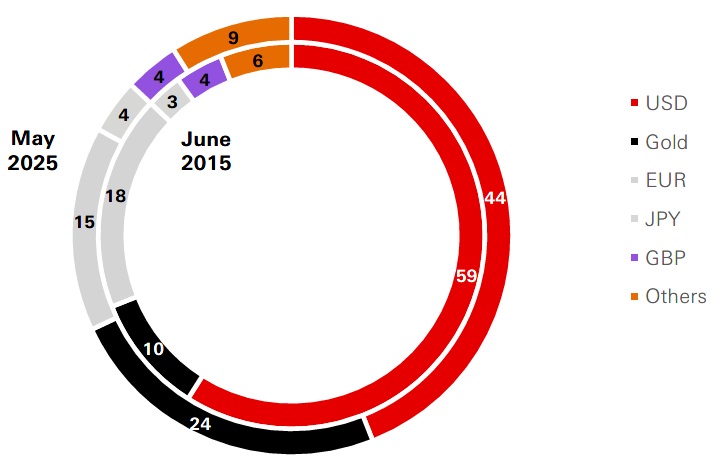

Over the past decade, dollar’s share of global reserves has declined by roughly 15 percentage points, falling to around 44 per cent. Crucially, this lost share has not gone to other fiat currencies but to gold. Central banks in Russia, China, Turkey, and India have been among the most aggressive buyers, reflecting a desire to hedge against sanctions, diversify reserves, and reduce reliance on US assets.

Figure 3: Gold gains reserves share (global, in per cent)

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg, US Treasury, US Fed, ECB, IMF COFER, SWIFT, BIS, Atlantic Council, September 2025.

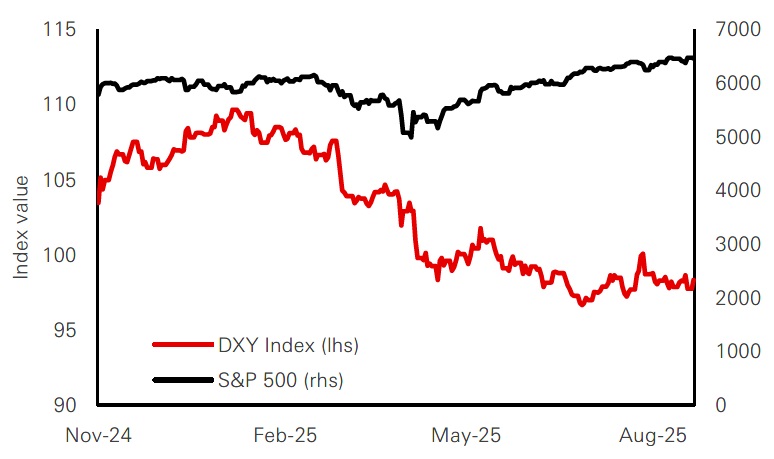

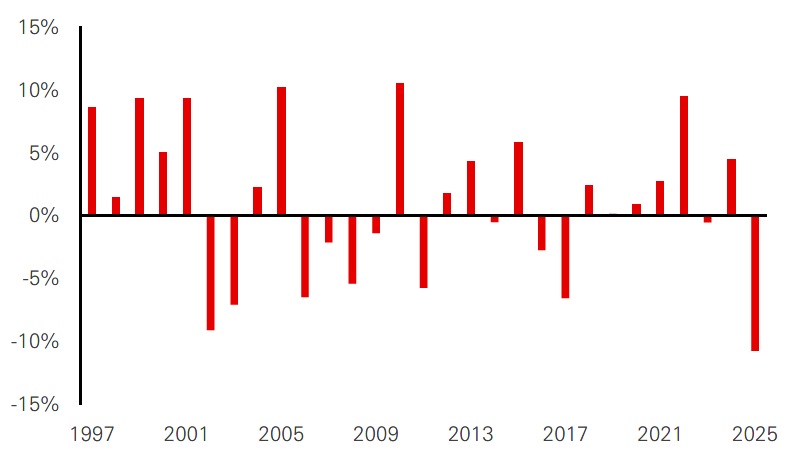

The dollar also faces headwinds from within. Following the most recent US presidential election, the US dollar experienced notable fluctuations in its performance, as reflected in the Dollar Index (DXY). Initially, the dollar saw a short-term rise in the aftermath of the election, driven by a temporary surge in market optimism. However, this was quickly followed by a sharp decline, marking one of the weakest performances for the dollar in the first half of the year when compared to similar periods over the past three decades.

Figure 4: US dollar vs S&P 500 performance since election

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 5: DXY performance for first half-year (6 month returns)

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns. Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of September 2025.

The key drivers behind this decline stems from geopolitical and economic developments. The US fiscal deficit has widened significantly, with debt levels ballooning. Moreover, trade tensions and the broader implications of protectionist policies created significant market unease, undermining investor confidence in the dollar. Political interference with the Federal Reserve has also raised concerns about the central bank’s independence. Together, all these factors have contributed to record-high short positions against the US dollar, reflecting the shaken confidence in the US as a steward of global stability.

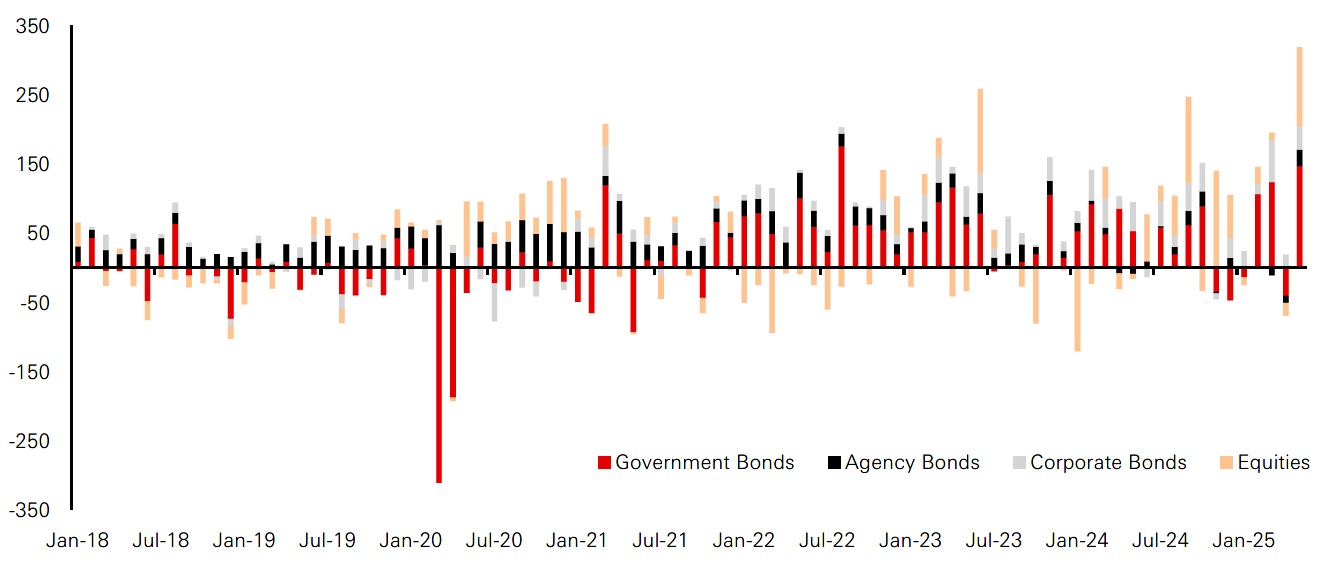

At the same time, speculative markets are divided. While short positions on the dollar have surged, foreign inflows into US assets – especially equities and Treasuries – remain robust. This means that there may be doubts about the dollar’s near-term trajectory, but interest in American markets remains strong.

Figure 6: Foreign net flows into long-term US assets (in USD bn)

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg, US Treasury, US Fed, ECB, IMF COFER, SWIFT, BIS, Atlantic Council, September 2025.

The deficit debate and fiscal risks

For decades, the US current account deficit has been a persistent feature. Traditional theory suggests that deficits necessitate borrowing, which in turn drives capital inflows. Alternatively, a capital-driven perspective argues that global investors’ appetite for US assets drives capital inflows first, which then strengthens the dollar and deepens the current account deficit.

Today, the capital-driven view appears more persuasive. The US offers deep, liquid markets that attract global savings. As long as foreign investors see value in Treasuries and equities, capital inflows will support the dollar despite structural trade imbalances. However, sustained uncertainty – whether fiscal, institutional, or geopolitical – could undermine this confidence and reverse the dynamic.

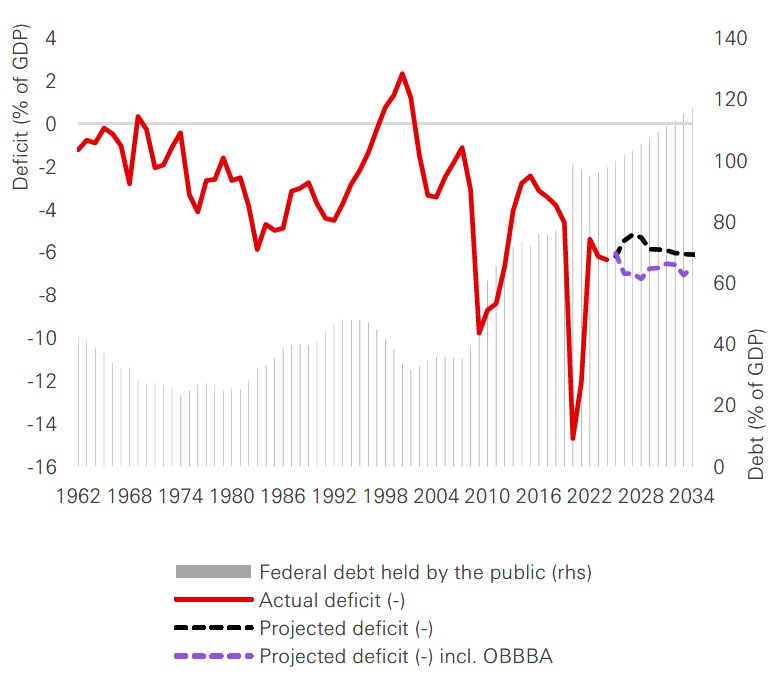

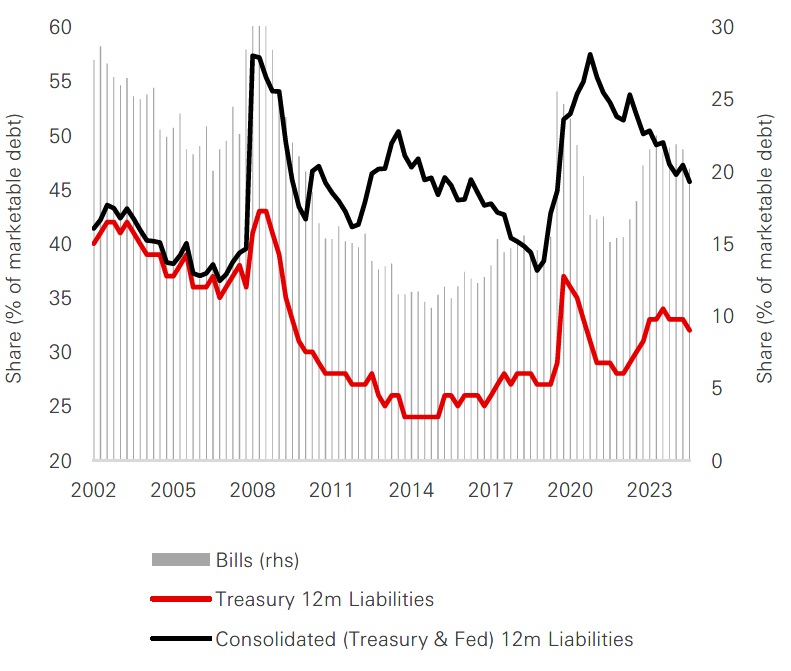

Another threat that looms large for the dollar’s long-term health is fiscal deficits and rising public debt. US debt held by the public has ballooned over the past six decades, with deficits now hovering near 6 per cent of GDP, and projections suggest further deterioration to 6.74 per cent by 2030. The US Treasury’s heavy reliance on short-term bills, rather than longer-term bonds, increases refinancing risks, especially if political gridlock or policy shocks disrupt confidence. While the proportion of bills as a percentage of marketable debt remains below historical averages, it is expected to rise to 27 per cent by 2027, approaching levels last seen during the global financial crisis. This shift could heighten the vulnerability of US debt markets to changes in investor sentiment and interest rate volatility.

Figure 7: CBO projected vs actual deficit and federal debt held by the public

Click the image to enlarge

Figure 8: Refinancing needs over next year and bills as per cent of marketable debt

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg, CBO, Fed. Data as of September 2025.

Overlaying this is concern about the Federal Reserve’s independence. Historical experience and IMF research show that central bank independence correlates strongly with stable growth and inflation. Political pressure to lower rates for short-term gain undermines this independence, as highlighted by episodes when presidential criticism of Fed leadership immediately triggered market volatility and dollar weakness. If the Fed’s autonomy erodes, the credibility of the dollar as a global safe-haven would be severely compromised.

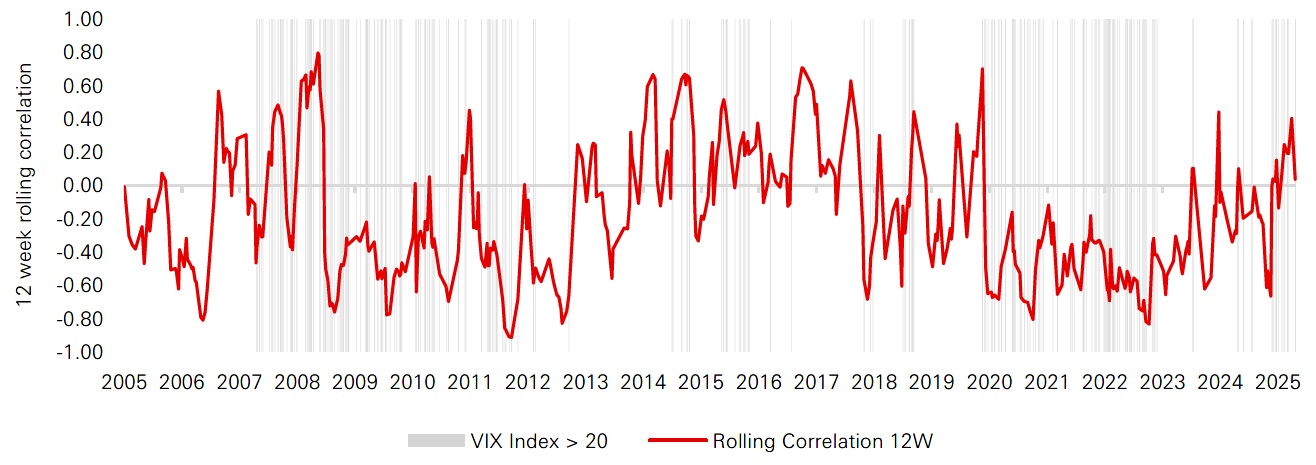

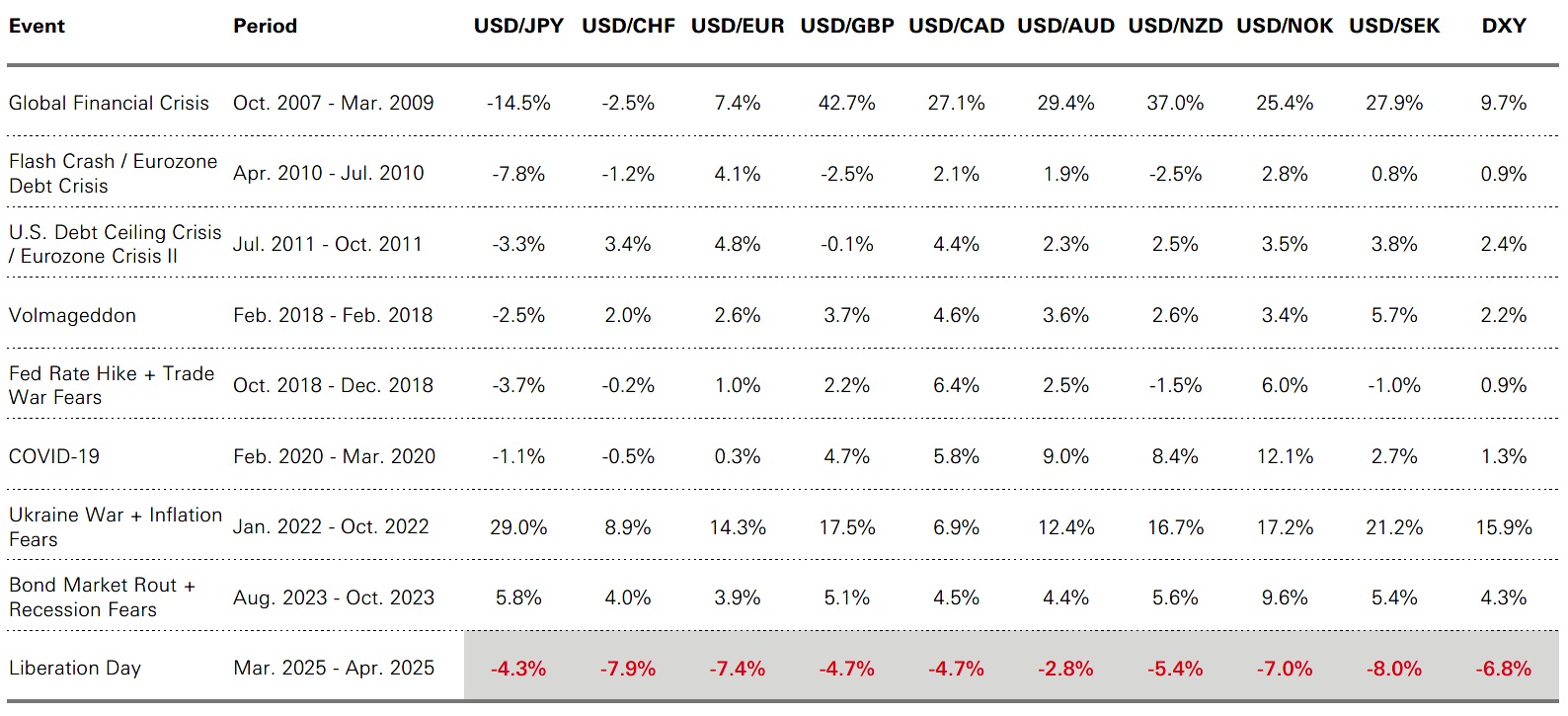

US dollar losing safe-haven status

Traditionally, the dollar has strengthened in risk-off episodes, serving as the ultimate safe-haven. It is revealed by an analysis of the rolling correlation between the Dollar and the S&P 500 Index which is negative during periods of heightened market volatility, as indicated by spikes in the VIX index above 20. Yet in 2025, correlations shifted. For the first time in years, the dollar’s movements were positively correlated with equities rather than providing diversification. During key stress events, such as ‘Liberation Day’, the dollar failed to deliver its typical hedge function, raising doubts about whether it can still be relied upon as a portfolio diversifier.

Figure 9: Rolling correlation between DXY and SPX

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of September 2025.

Further evidence of this shift can be seen in the performance of the dollar relative to other safe-haven currencies, such as the Japanese yen (JPY) and the Swiss franc (CHF). During recent risk-off episodes, the dollar underperformed these currencies, raising questions about its ability to maintain its traditional role in times of crisis.

Figure 10: USD versus other currencies in a risk-off environment

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns. Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of September 2025.

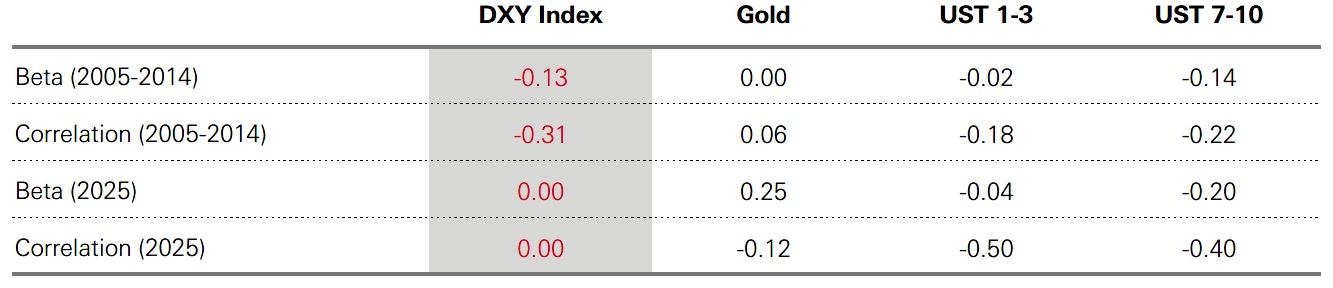

By contrast, gold preserved its safe-haven appeal. This trend has been particularly evident in 2025, where gold has delivered strong returns amidst global uncertainty, further challenging the dollar's dominance in this space. Central bank accumulation of gold also underscores this trend. If the dollar continues to lose its hedging power, gold and potentially other diversifiers could play a larger role in global reserve strategies.

Figure 11: Betas and correlation with SPX

Click the image to enlarge

Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of September 2025.

Market sentiment and signals

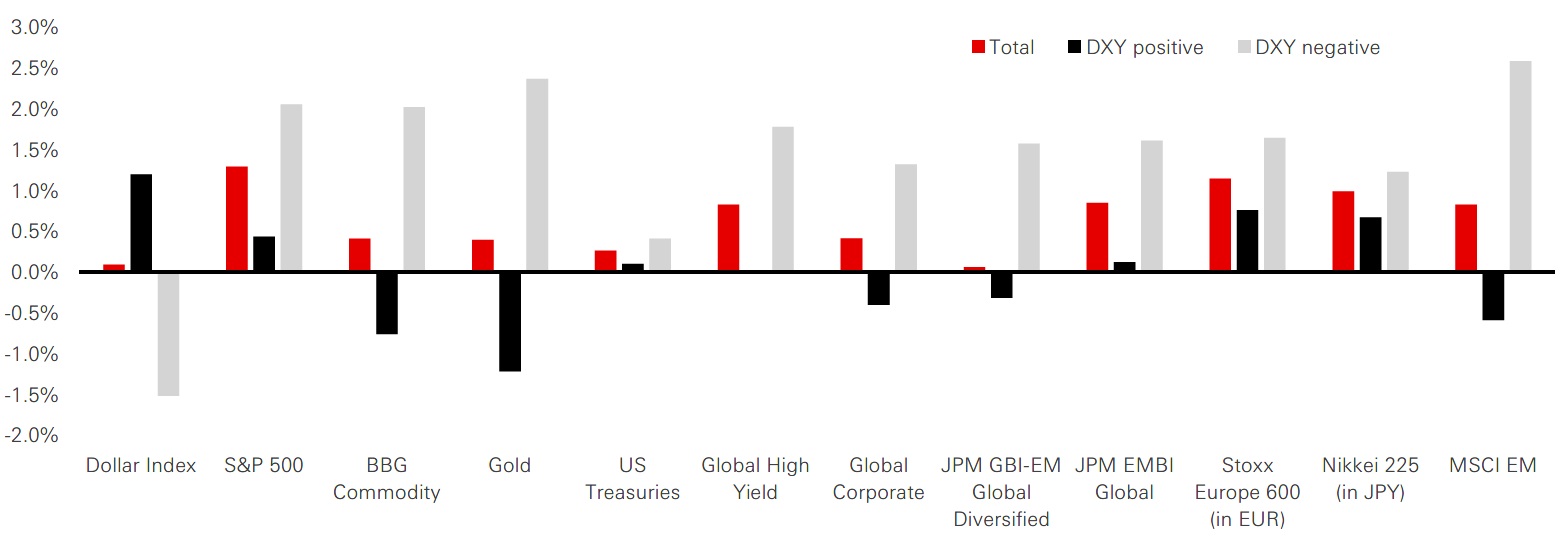

The dollar has been a powerful driver of asset performance since 1999. Dollar bull markets have typically weighed on commodities, gold, and emerging market assets, while developed market equities, particularly the S&P 500, have shown resilience. Conversely, dollar bear markets have consistently favoured commodities, gold, and emerging markets, with both equities and fixed income benefitting from weaker funding costs. This pattern of commodities and EM corporate bonds having strongest negative relationship with the dollar index is confirmed by their sensitivity to dollar swings. Today, this dynamic is especially relevant – any sustained dollar decline could provide a significant tailwind for emerging markets.

Figure 12: Median monthly returns

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns. Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of September 2025.

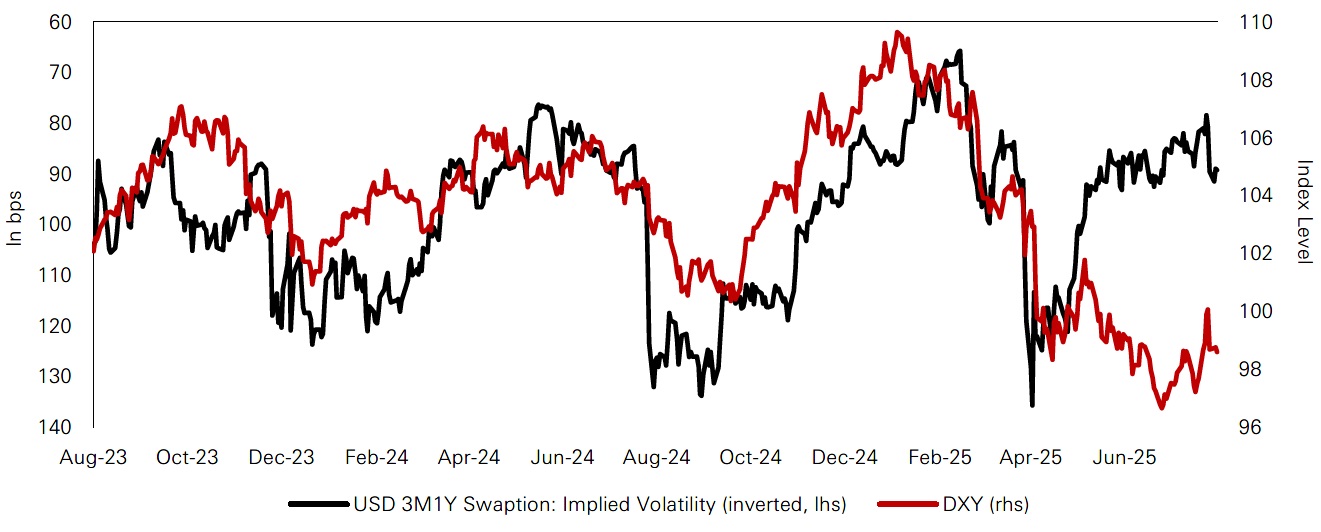

Options and derivatives markets provide another window into these shifting dynamics. For much of the past decade, hedging against dollar weakness was cheap; now, dollar puts trade at a premium to calls, signalling growing investor concern about depreciation. Moreover, declining interest rate volatility had historically supported the dollar, as policy clarity reduced uncertainty. Yet this relationship has broken down in recent months as reflected by the dollar failing to strengthen despite falling volatility.

Figure 13: USD versus US rates volatility

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns. Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg. Data as of September 2025.

Similarly, risk reversals in EUR/USD and GBP/USD have flipped positive, signalling that investors now see greater need to hedge against dollar weakness than against appreciation. Collectively, these signals point towards the changing sentiment around dollar.

Figure 14: Cross-currency bases vs USD

Click the image to enlarge

Past performance does not predict future returns. Source: HSBC AM, Bloomberg, BIS. Data as of September 2025.

Cross-currency basis trends further hint at waning demand for US assets, possibly reflecting reduced FX-hedged flows from foreign institutions. If confirmed, this would erode one of the key pillars supporting the dollar’s dominance.

Implications and preparing for a multipolar currency world

The US dollar, while still the world's dominant currency, is showing signs of strain. Historically, globally dominant currencies have lasted 80-100 years, and the dollar is nearing the upper limit of this range. Although its collapse is not imminent, its long-term dominance is not guaranteed. The dollar retains significant advantages that could sustain its role for decades, but its position is gradually weakening. Key factors to monitor include Federal Reserve independence, fiscal policy, and global diversification of reserve currencies, all of which will shape the dollar's trajectory in the years to come.

For investors, the key takeaway is that dollar dominance is not binary. It is not about collapse versus supremacy, but about gradual shifts that change the risk-return profile of portfolios. This means that the challenge is not to predict the exact moment of transition but to prepare portfolios for a world where the dollar is strong, but not unassailable.

If the dollar’s safe-haven appeal is waning, portfolios may need greater allocations to gold, alternative currencies, or non-dollar assets. Emerging markets, in particular, stand to benefit from dollar weakness, as history shows they tend to outperform in dollar bear markets.

Source: HSBC Asset Management, October 2025. Diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against loss. The views expressed above were held at the time of preparation and are subject to change without notice. For informational purposes only and should not be construed as a recommendation to invest in the specific country, product, strategy, sector or security. Any forecast, projection or target where provided is indicative only and not guaranteed in any way. HSBC Asset Management accepts no liability for any failure to meet such forecast, projection or target.